Archives of Abuse

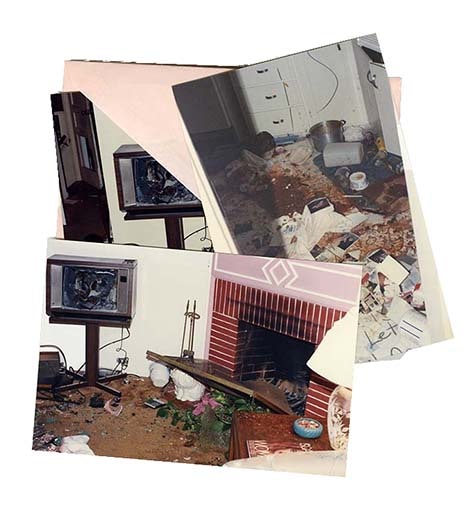

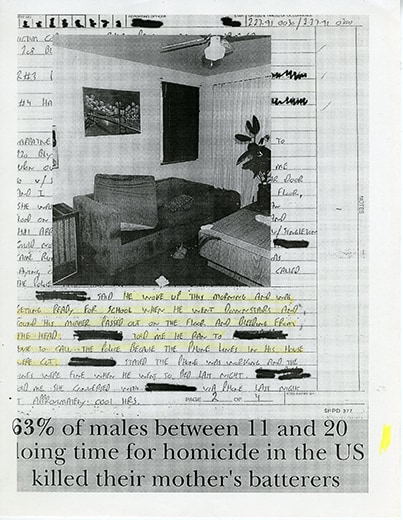

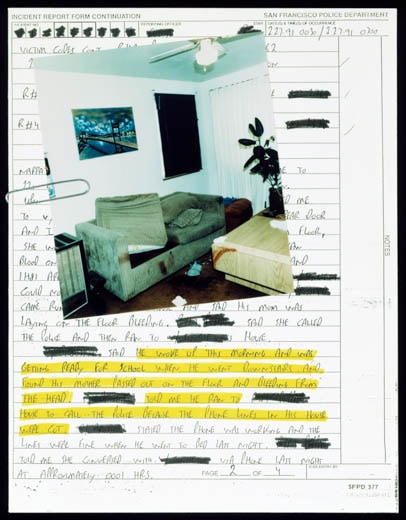

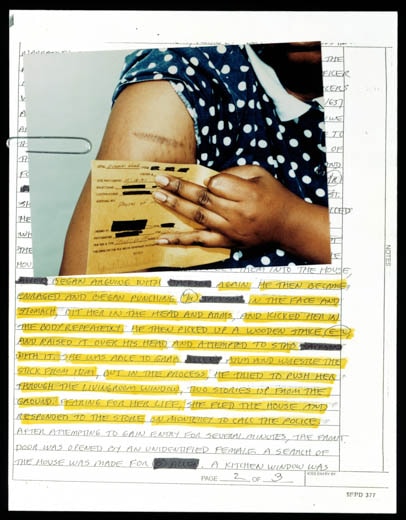

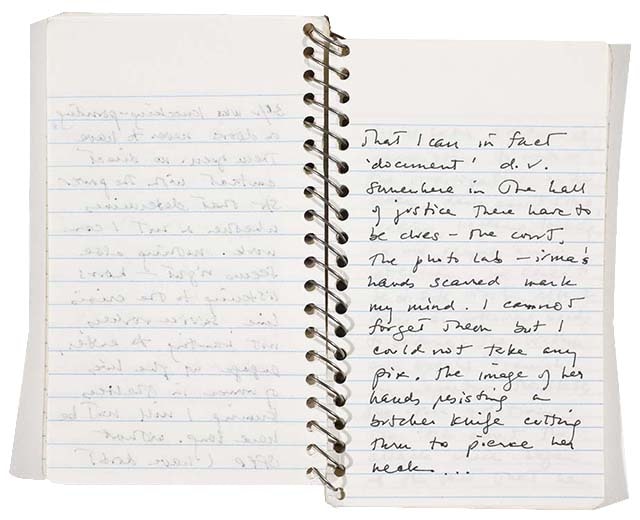

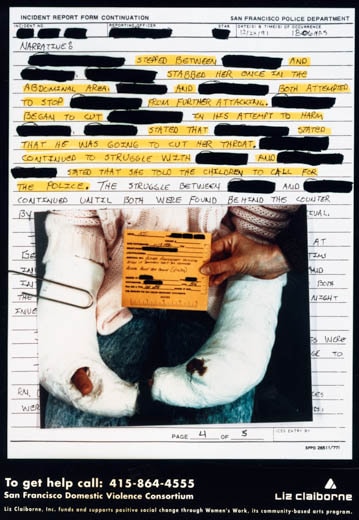

My past work has led me to look at the wars that we wage against one another -- whether in the streets of Central American or the homes of San Francisco -- I feel the necessity to be as close as an outsider can be. I chose to work with the San Francisco Police Department, to be present at the moment of their intervention, to observe the process of documentation and mediation, while respecting and protecting the identity of the victims. The records gathered revealed a history of scars that were beyond what I ever might have imagined or pictured.

-SM, 1992 (in a letter to Lynne Sowder, Producer of Women's Work, a project supported by Liz Claiborne Inc.)

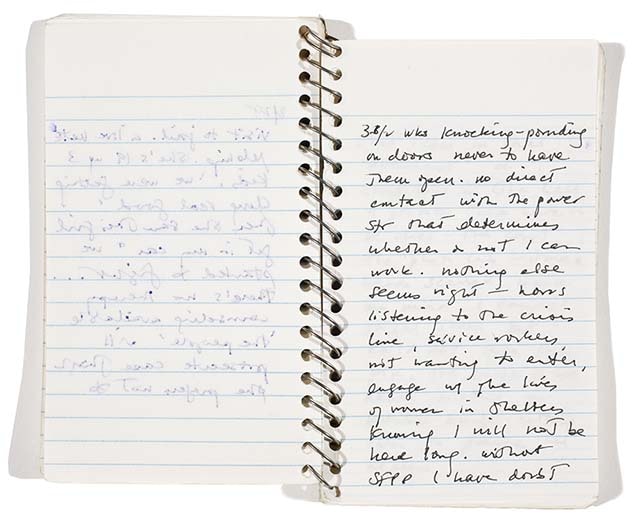

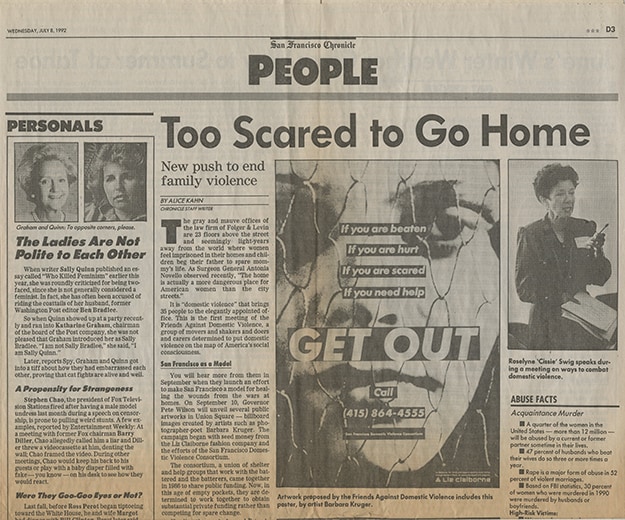

In 1990, the Liz Claiborne Foundation invited me and five other artists to work on billboard and bus shelter ads for a campaign in San Francisco to raise public awareness about domestic violence. As a documentary photographer, my instinct was to find a way to work with the police. Essentially, I hit a brick wall. I was hanging around the police station, trying to get information. I saw their reports were accumulating in folders on their desks and I began to read them and ask questions.

I had been paired up with a specialized investigative team that goes back to the domestic violence crime scenes and tries to gather additional information from witnesses. I asked them permission to go out with them to get a sense of what they were up against.

-SM

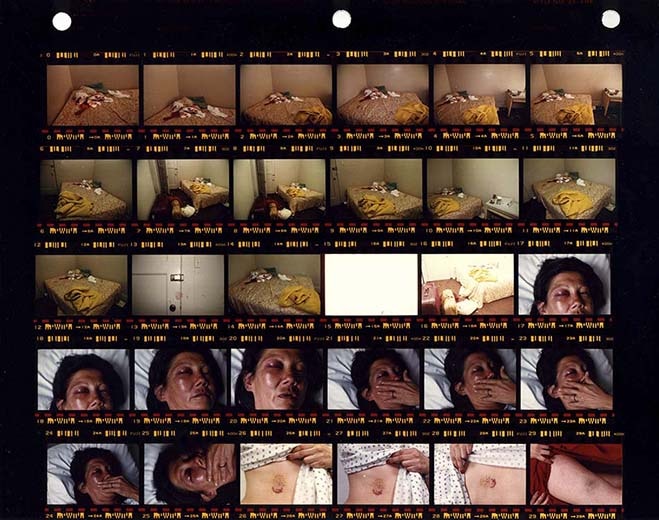

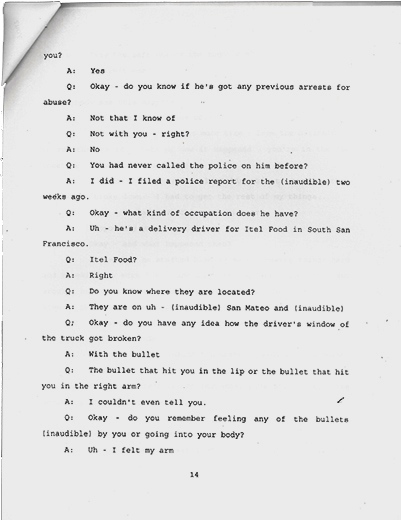

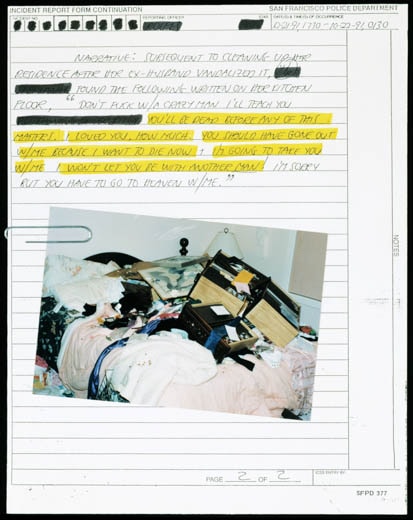

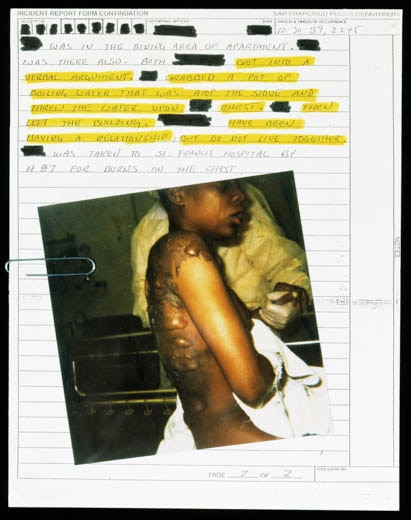

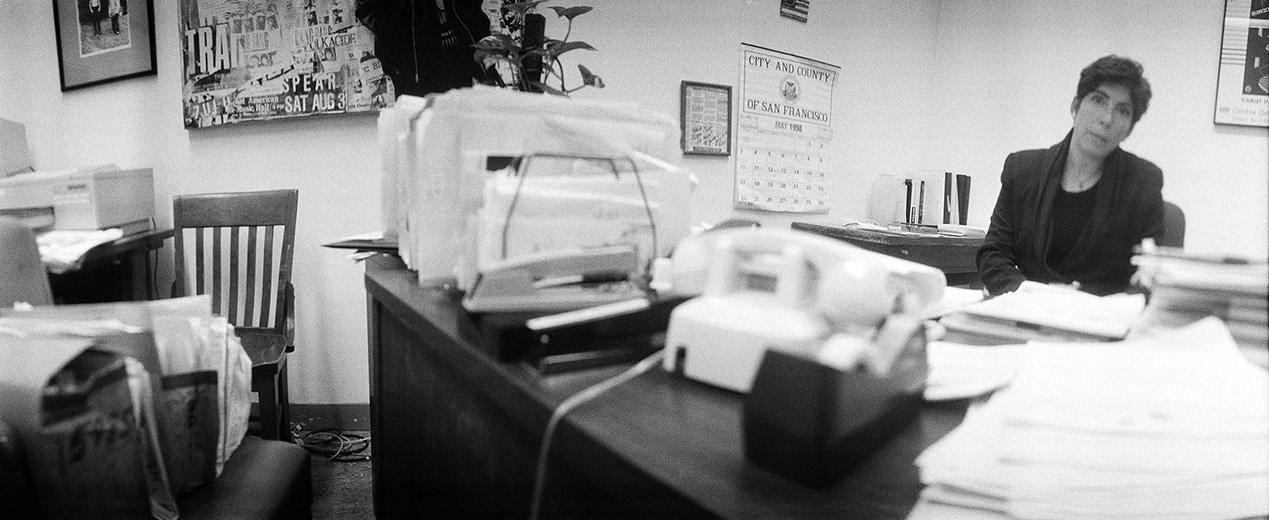

I remember arriving with them at the scene of a homicide in a small hotel downtown and watching the police photographer at work. I was frustrated at not being permitted to take pictures myself. But I was given permission to select the reports that I found most interesting and to look at the photographic evidence that accompanied them. I decided to work with what already existed, instead of generating my own photographs. Then I agreed to go back to the victims and get their permission to use this material for my collages. Susan Breall, at the San Francisco's D.A.'s office, contacted the women and arranged for me to go to their homes and talk to them.

- SM

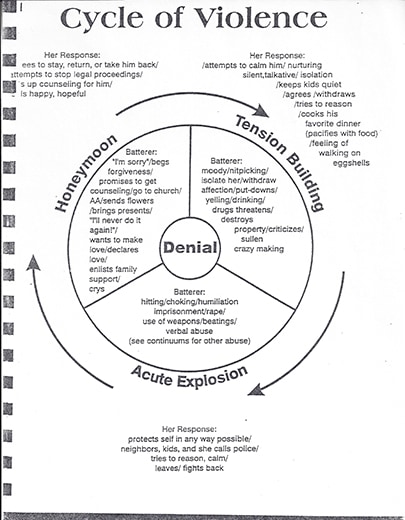

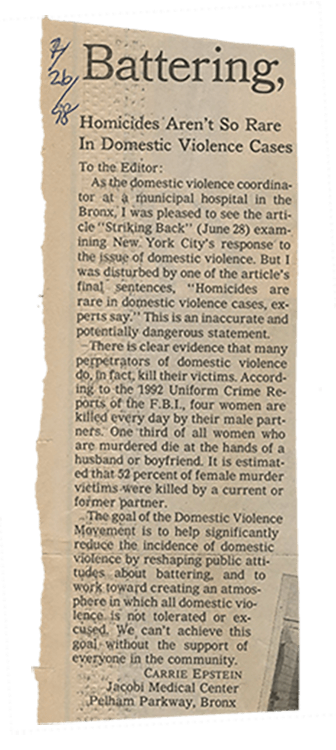

In my experience, domestic violence is a pattern offense. The literature talks about the "cycle of violence," and about "battered women's syndrome." There may or may not be a typical battered woman, but in my experience, there is a cycle and it happens over and over again. There's the honeymoon stage when things are really wonderful, and there's the stage when the tension builds, and then there's the eruption of the violence and then you make up. Usually that's right at the time you're about to go to trial, and he is calling her from jail, and then they're getting married in the holding cell by the judge who's about to be the presiding judge on the case.

- Susan Breall, Assistant District Attorney

San Francisco District Attorney's Office

I've prosecuted domestic violence cases for more than eight years, and in that time I've seen women who have been beaten and raped. I've seen women who have been burned, I've seen women who have tried to jump out of fourth-floor windows to escape their batterers. I've seen women who've had men leave marks on their bodies in places that most people will never see. And I've seen these same women have the courage somehow to come to court, and talk about what happened to them. The only thing you have going for you when you are in court is the emotional impact of the stories. I tell each woman it's going to be your word against his word, and we need to take this crime and stretch it out in slow motion. You have to make this come alive for me so I can make it come alive for the jury.

When you get a conviction, it's not like you go out and whoot it up. There's this sadness that you have had to go through all this, just to get one word: guilty. It means punishment, incarceration. Here's this young man, in his twenties, he's going to spend his life in state prison. Here's this young woman, and she'll have physical and emotional scars for the rest of her life. The conviction is a validation of what she went through, but it's not some wonderful thing for her. I am very satisfied when I get one. I feel it is fair but I do not feel like celebrating.

- Susan Breall, Assistant District Attorney

San Francisco District Attorney's Office

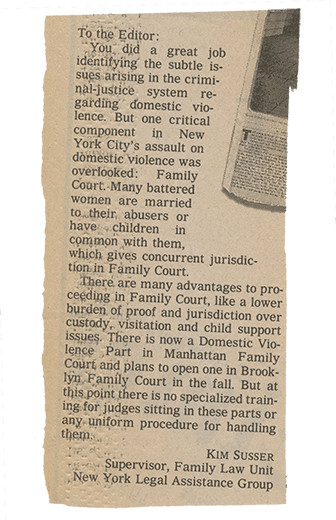

You are almost not the victim, you are almost the cause of the crime. There are a lot of games society plays with you. The person who stabbed me, because he had three strikes, he got one of the best lawyers in San Francisco, pro bono. His lawyer was an ex-policeman, a very, very good lawyer, and they didn't think what was done to me was serious. The defense investigator used to come over to my house and talk to me, ask not to press charges. The things that I had to go through until the day that person was sentenced were humiliating. The police would ask me, if I was afraid of this person, why did I allow him around me? They investigate your personal background--where I met him, the length of time the relationship went on--and they let you know that that's what they're doing. You cannot be intimidated.

In the beginning, I believed in the law, but I didn't know how the law worked, and it was really surprising. I got stabbed in August 1992, I think. It took a year for the police to find cause that he had actually stabbed me. I had been going to court that whole time. I felt that he had more rights than I did, even though he was locked up. His lawyer tried to break me down. They wanted to know what I did wrong to have him do something like that to me. I mean, what do you do wrong to be stabbed six times in your car?

-Noline

I always intended to return to this project. Several months ago, I began to interview the women I had met in 1992. I was somewhat intimidated to go back to the survivors and ask them to speak again about these experiences, which have been so painful for them. I went cautiously and took it quite slowly. It's taken time to be comfortable with what it means to open up scar tissue.

- SM

When Susan needed waivers from these women for her project, I contacted them and arranged for her to meet with them. Just talking to them on the phone, years after their experience, was amazing. I accompanied her to the home of one of them - the woman in the photo who had been so badly burned. Going to see this woman, two years after I had prosecuted her case, and seeing how her life had changed, how she had moved on, was incredibly moving. It's something a DA rarely does. These women affect you, but you don't know how you have affected them. I've been to women's houses since, and kept in touch with some of them. It has nothing to do with being a prosecutor - you have to love learning about women's lives.

- Susan Breall, Assistant District Attorney

San Francisco District Attorney's Office

Archives of Abuse is part of a series of work that Meiselas has done revolving around domestic Violence throughout her career. Most recently, she was was invited to the Black Country in England to make work about the region by Multistory, a non-profit local arts organization. There Susan worked with women living in refuge after leaving abusive relationships or circumstances. This project, A Room of Their Room, is a look at the next phase of the recovery process for those affected by domestic violence globally.