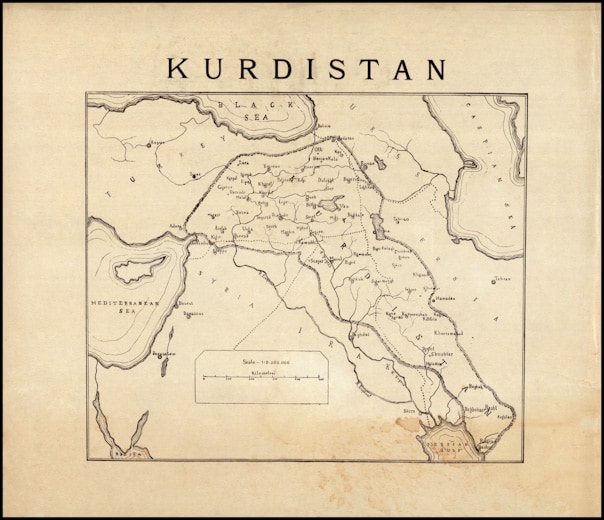

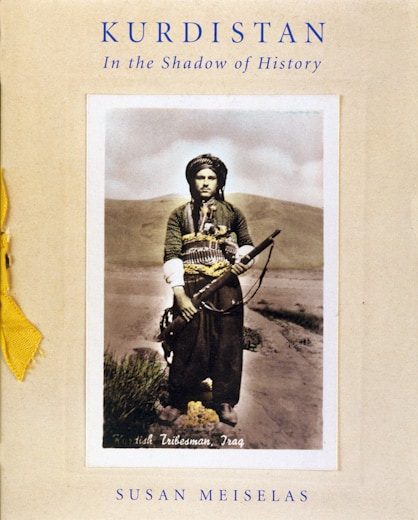

Kurdistan

When the Gulf War began, I, like most Americans, knew little about the Kurds. My first visit to the region was brief. Pleased to have the Western press witness the Kurds' pressing need for humanitarian aid, Iran granted me a five-day visa and access to the Kurdish refugee camps. It was barely enough time to leave Paris, cross the Iranian border and get to the "liberated" zone within Northern Iraq. While the world's attention was concentrated on the flight of the Kurds, I was drawn to the places from which they'd came. I drove in along the same road upon which many Kurds were still fleeing.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

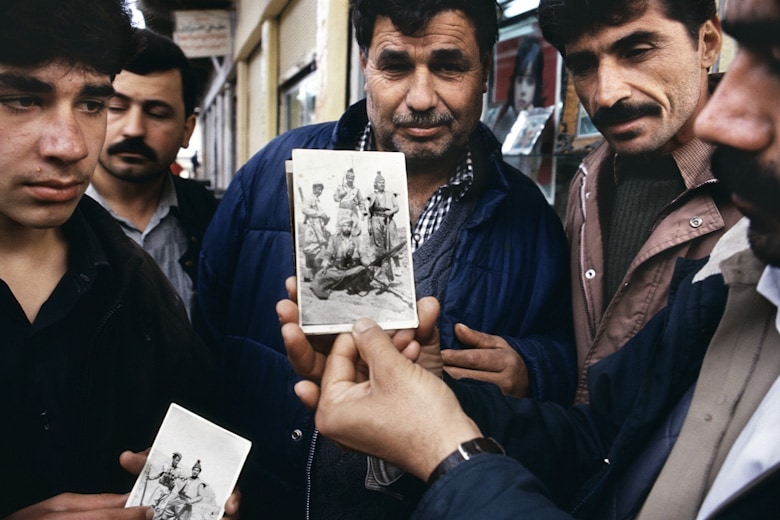

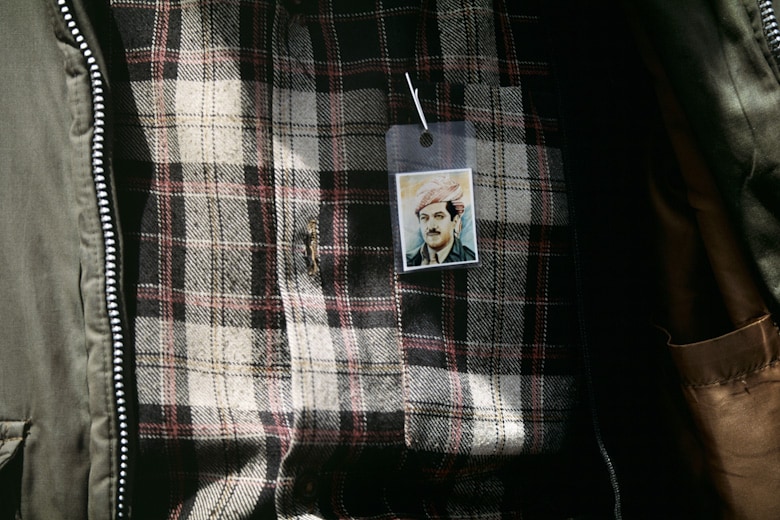

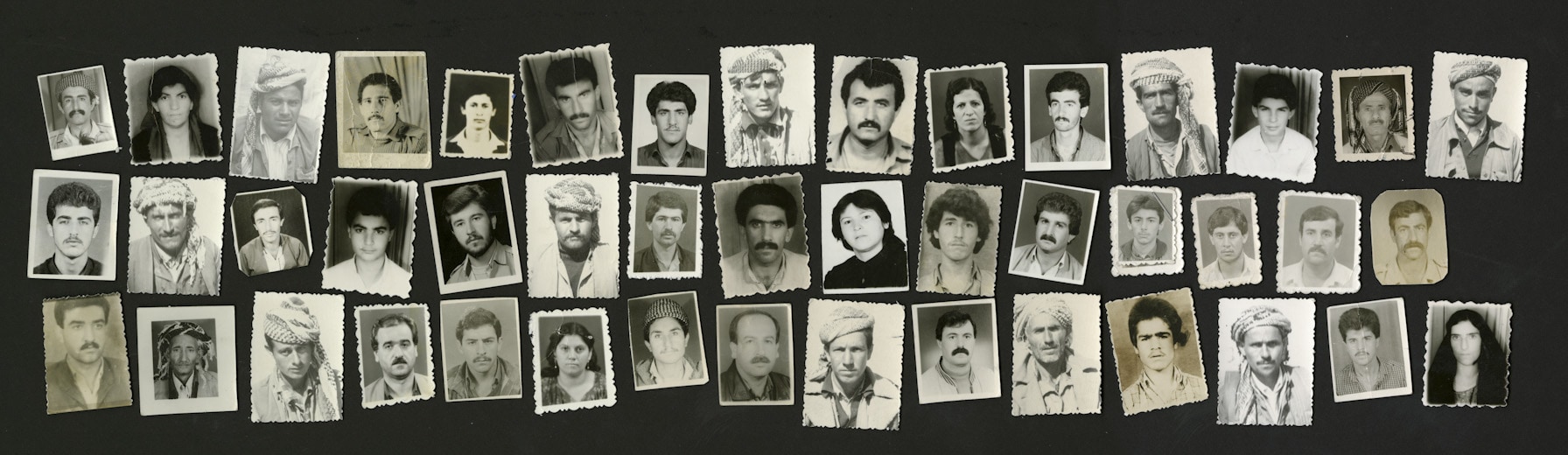

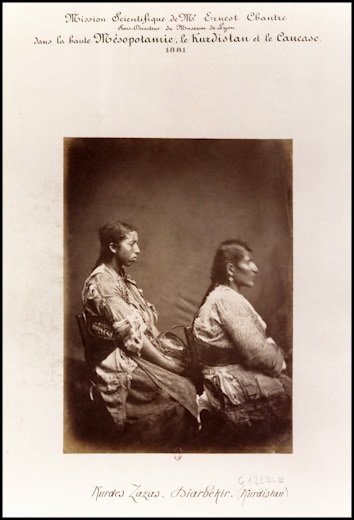

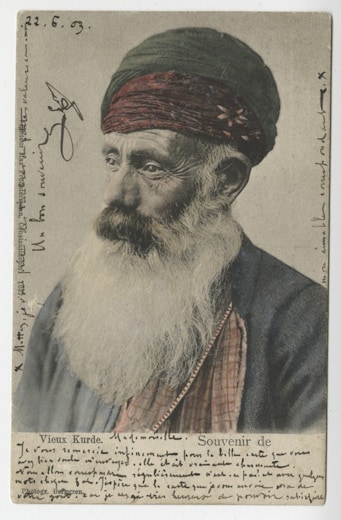

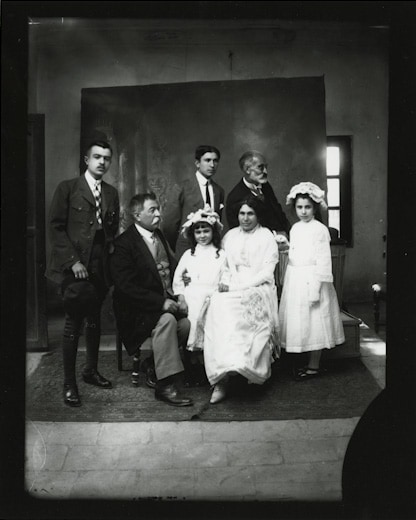

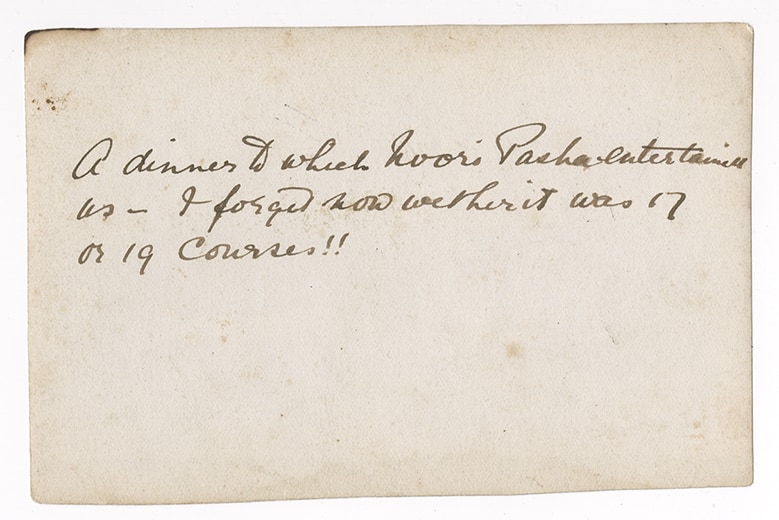

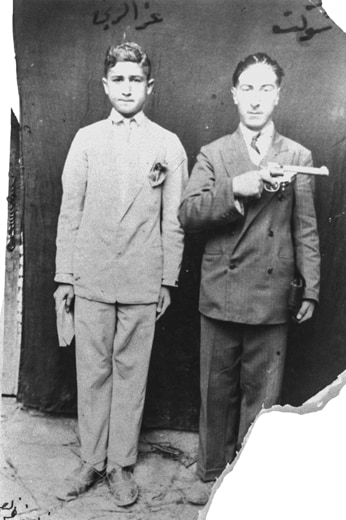

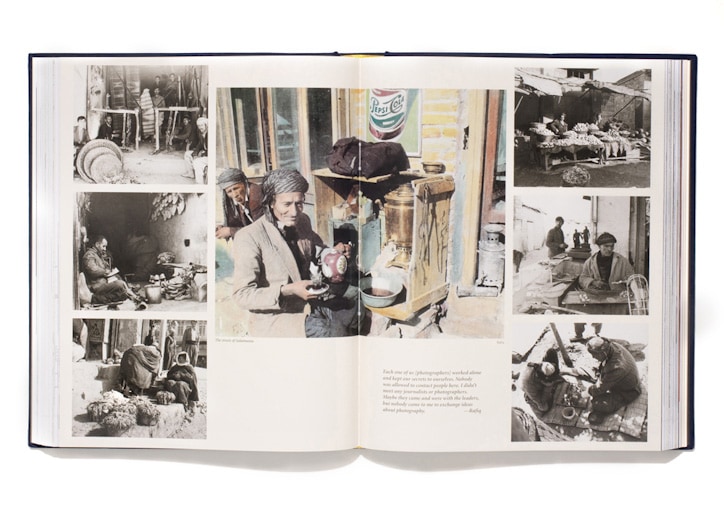

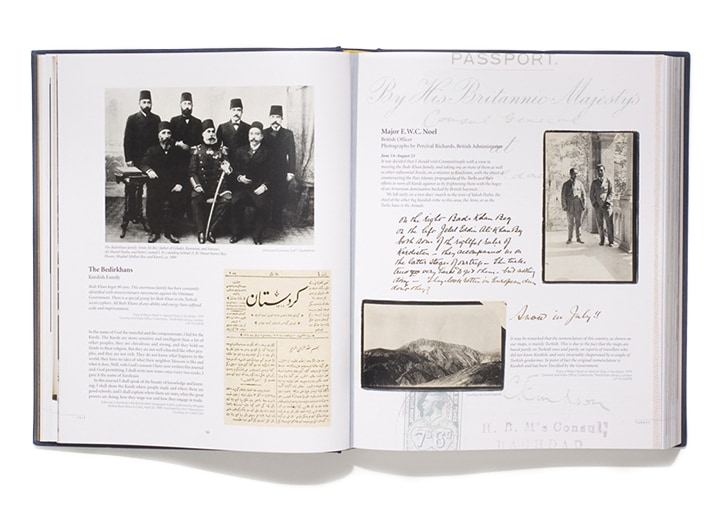

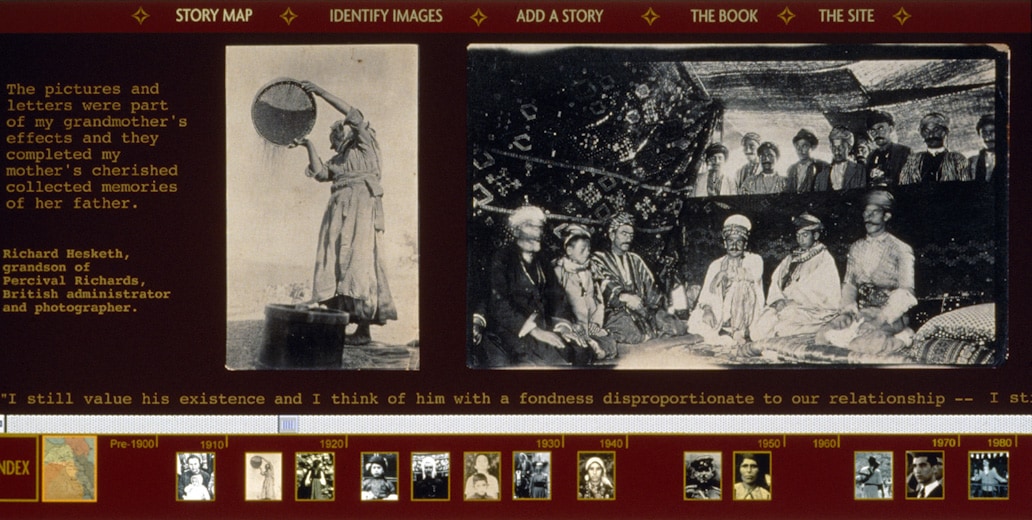

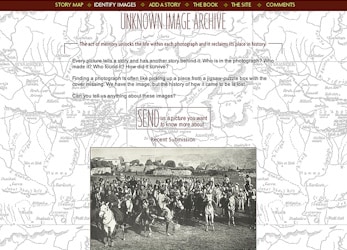

Every picture tells a story and has another story behind it: Who's photographed? Who made it? Who found it? How did it survive? I wonder what we can know of any particular encounter by looking at such a picture today. We have the object, but it exists separated from the narrative of its making.

What interested me was the intersection and interplay between those who shaped Kurdish life and the lives of the chroniclers who pictured them -- the photographers and those photographed, the points of cultural exchange, how the various protagonists crossed one another's paths. Both left their marks on Kurdish history.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

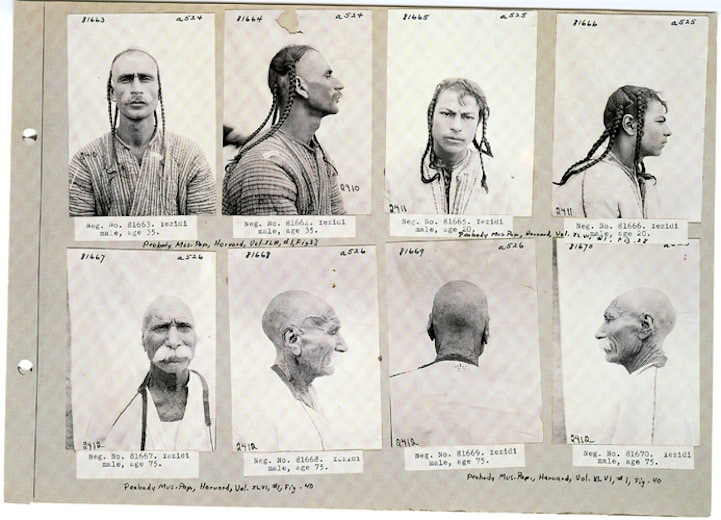

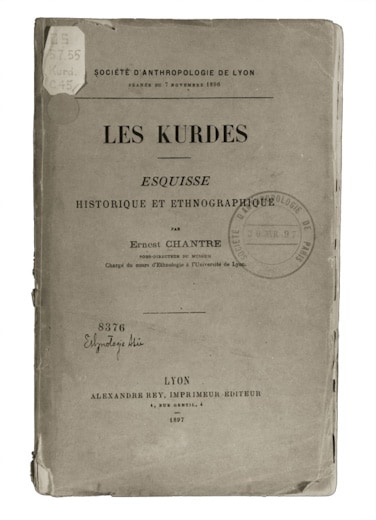

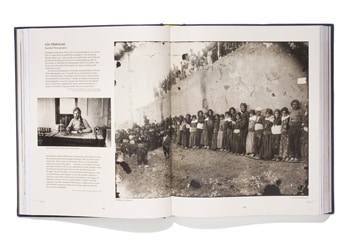

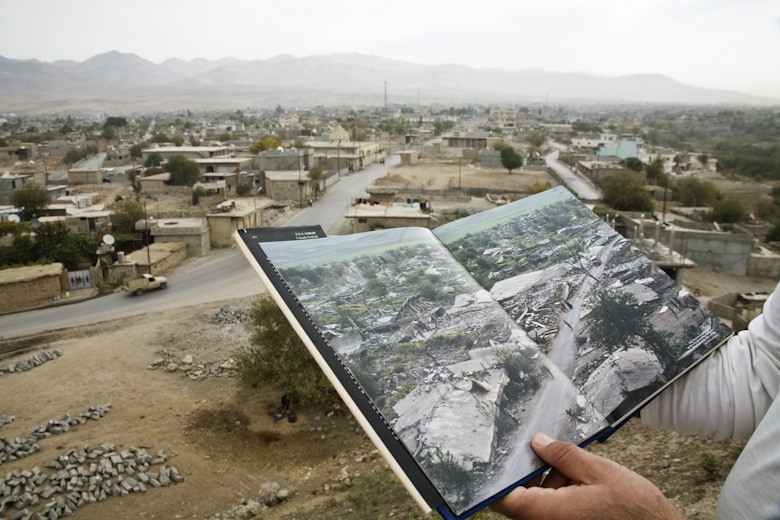

Some Kurds know a lot about those who passed through their lands over the past century. The names of Western travelers, missionaries, military officers, and colonial administrators float among the names of their own Kurdish heroes...Other Kurds told me that they had read some of the Western memoirs written about them. Dusty books, sparsely illustrated, long out of print, were taken off back shelves in their homes and proudly shown to me as treasured accounts. Thumbing through the pages, I thought about all the photographs that had been made and then taken away from Kurdistan...I began to wonder where those early photographs were, imagining the route of their travel -- carried by hand as glass or nitrate negatives, or shipped in trunks -- to be pasted into albums or relegated to archives, or to disappear into attics.

In Western archives, the word "Kurdistan" is rarely indexed. The Kurds are catalogued according to the countries in which they live as minorities; most often they appear in archival indexes as "ethnic types." In each collection the classification varies; the photograph is seen as ethnographic description or aesthetic object, especially if it was made by a renowned photographer. Rarely is there any historical information about the people who are pictured and then categorized. But the image still stands as evidence of the encounter.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

Over time, my role divided between maker and collector. I stopped taking photographs, except to reproduce existing family photos with a Polaroid system. I felt immense pleasure sitting with families, first peeling off a positive image, then watching with my host as the negative appeared in the tray of sodium solution. Their precious originals stayed with them, but they allowed us to make copies to take away. These were privileged moments: to be invited inside, to listen to the storytellers, then to eat and sleep on their floors. Everywhere we were strangers, yet we were welcomed with trust as soon as people understood that they were contributing to a collective memory.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

Every picture tells a story and has another story behind it: Who's photographed? Who made it? Who found it? How did it survive? I wonder what we can know of any particular encounter by looking at such a picture today. We have the object, but it exists separated from the narrative of its making.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

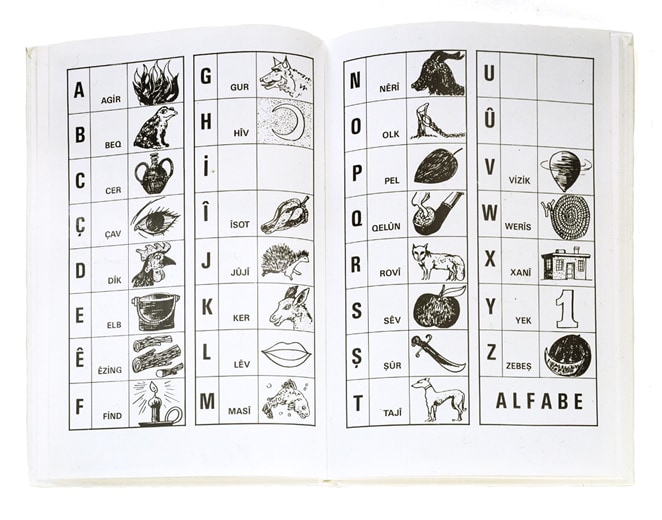

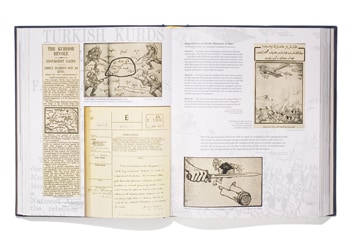

In the present work I've tried to re-create the Kurds' encounter with the West and ask readers to engage in the discovery of a people from a distant place without knowing exactly where that process will lead. In no way is this a definitive history of the Kurds. Texts and images are presented as fragments, to expose the inherent partiality of our knowledge. This is a book of quotations, with multiple and interwoven narratives taken from primary sources -- the raw materials from which history is constructed.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

Excerpts from diaries and documents make public what was often a personal record or private exchange. Suggesting the randomness by which history gets made, newspaper clippings and selected bits of memoirs reveal what was presented by the media and commonly believed at the time. Rather than emerging as a completed puzzle with every piece fitting neatly together, this book project has revealed a mosaic -- only from a distance is there a shape to discern. This is a reconstruction based on what remains and has been retrieved; we cannot know what is gone. Certainly, much is missing.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

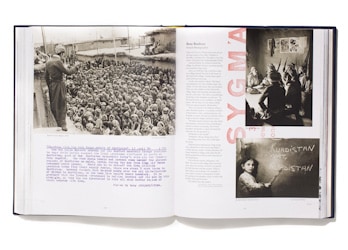

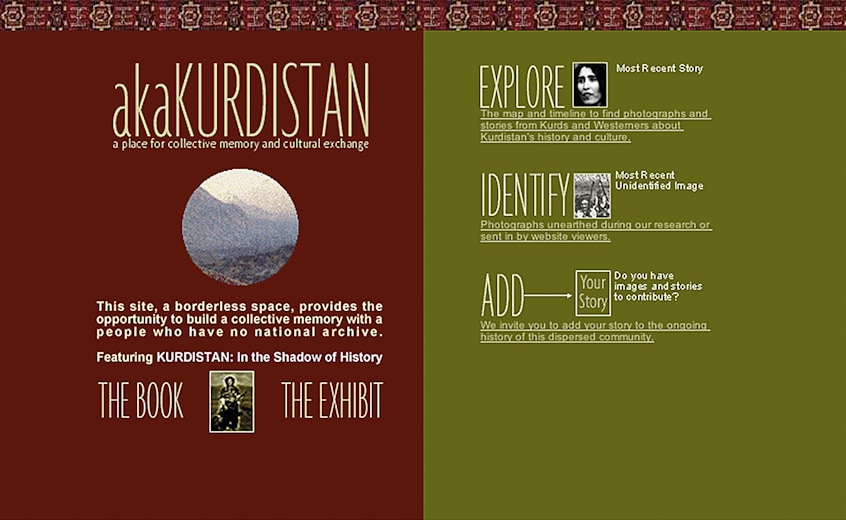

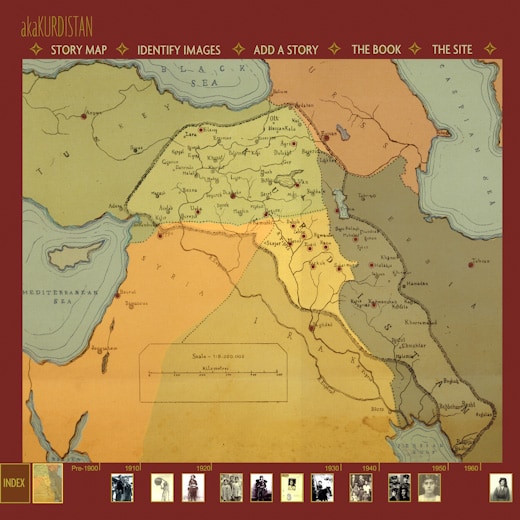

The site akaKurdistan functioned as an extension of the book project and a borderless space, providing the opportunity to build a living, collective memory with a people who have no national archive. Unidentified photographs, unearthed during research for the book and pictures submitted by internet viewers, were presented alongside the stories behind the images.

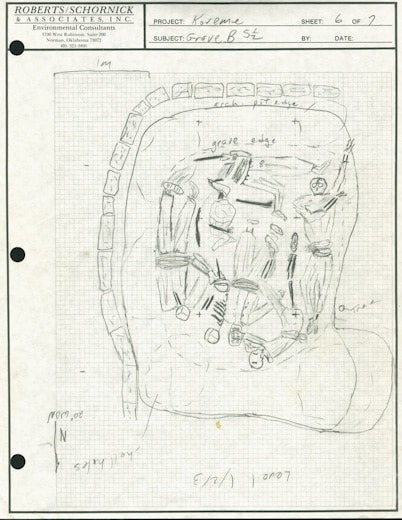

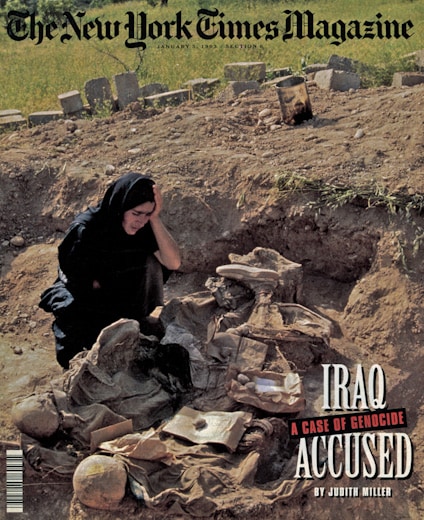

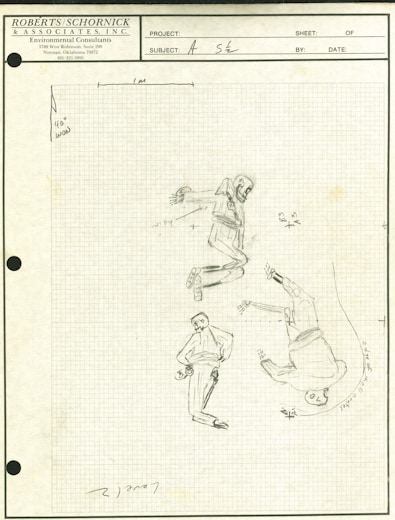

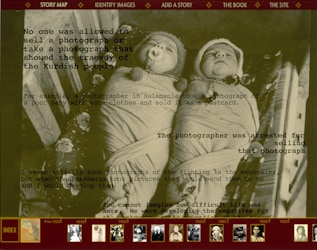

NORTHERN IRAQ. Kurdistan. 1991. Taymour Abdullah, age 15, shows his wounds to prove his story of escape from a mass killing. When he was 10, Iraqi army units entered his village of Qulojeo, near Kifre, and forcibly removed all inhabitants claiming to be relocating them to a model village. After a brief stay at an army base, his family and neighbors were driven in closed vehicles to a place near the Saudi Arabian border. There, they were blindfolded and told to enter a pre-dug trench. Machine guns then opened fire. Although wounded in the shoulder and back, Abdul managed to run away under the cover of darkness just before bulldozers covered the mass grave. A day later he was found and saved by Bedouin tribesman who protected him for two years.

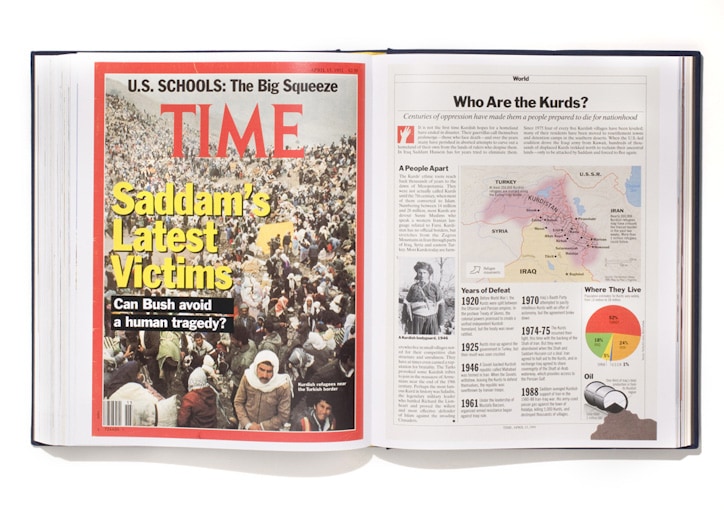

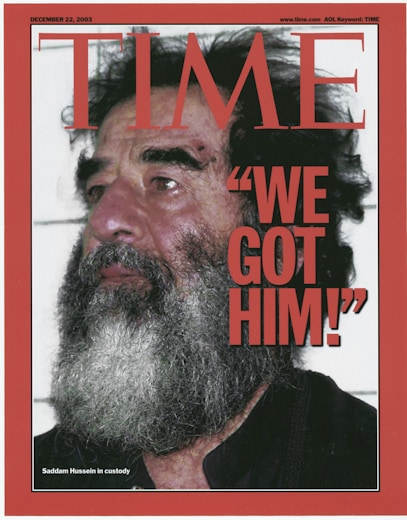

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, the White House exhibited a relentless determination to find evidence linking Saddam Hussein and al Qaeda. In the prelude to war, the Anfal campaign and the gassing of the Kurds were repeatedly cited as additional evidence of the evil nature of Saddam’s regime. The Kurds were America’s most significant allies inside Iraq, and their participation in the war greatly strengthened their bargaining position, giving them for the first time in history a decisive voice in charting the future of Iraq. The American offensive destroyed the regime, and much of Iraqi society along with it; Saddam went into hiding, was hunted down, captured, and publicly humiliated. His American captors then handed him to a specially established Iraqi court that tried him and his closest collaborators on various charges, including genocide of the Kurds.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

Saddam was sentenced to death for a massacre of Shiites and executed before the Kurdish trial had run its course; but the trial continued with the official who planned and organized the Anfal, Saddam’s cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid, as the chief defendant. Testimonies from Taymour Abdullah, along with scores of other Kurdish victims and witnesses of the Anfal campaign were gathered as evidence. Al-Majid was convicted in June 2007 and sentenced to hang.

-S.M. from "Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History"

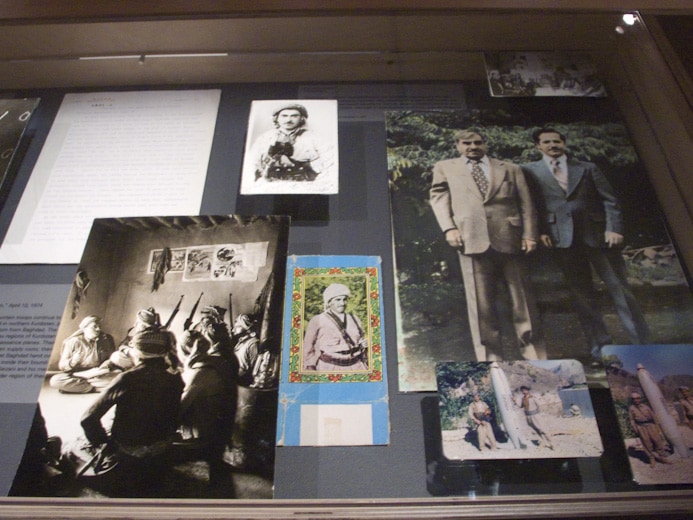

Installation views of akaKurdistan from different international exhibitions. The project has been shown at the International Center of Photography in New York (excerpt), el Centro Cultural Conde Duque in Madrid, the Nederlands Foto Instituut in Rotterdam, the Gwangju Biennial in South Korea and at many other cultural institutions, galleries and museums around the world.

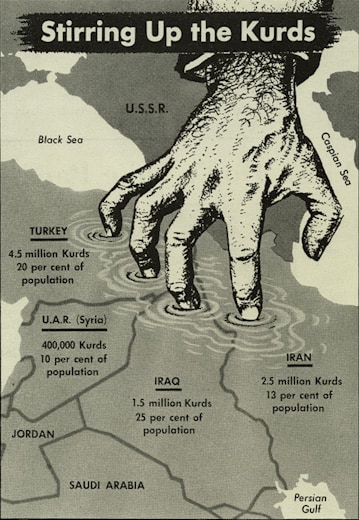

Today "Kurdistan" does not exist on the map. Since 1918, the Kurds' homeland has remained divided among Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria, and what is now the former U.S.S.R. In each country the Kurds have been continuously threatened with either assimilation or extermination. But as a place, Kurdistan exists in the minds of more than twenty million people, the largest ethnic people in the world without a state of its own.