Mediations

MEDIATIONS

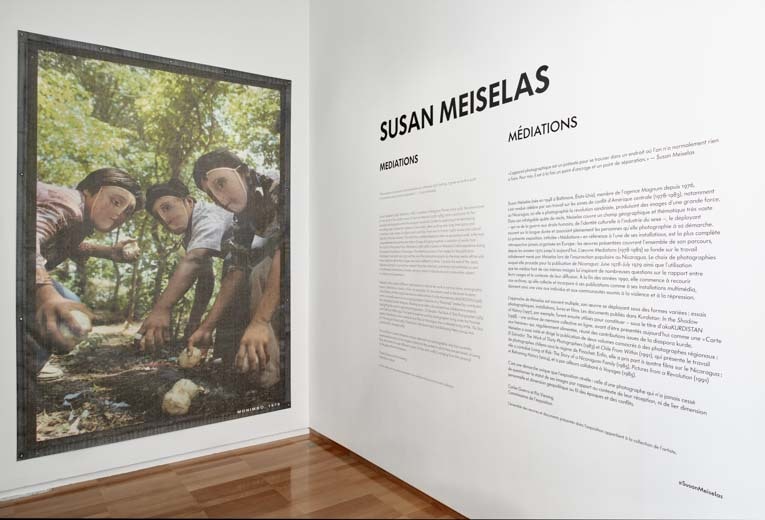

“The camera is an excuse to be someplace you otherwise don’t belong. It gives me both a point of connection and a point of separation.” — Susan Meiselas

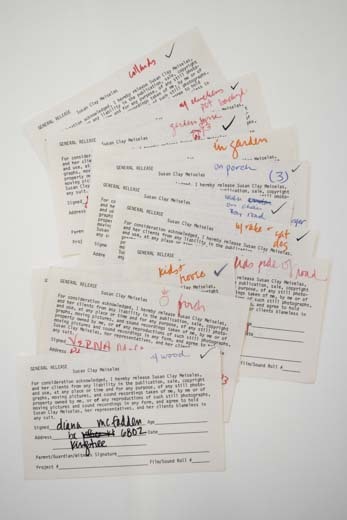

Susan Meiselas (1948, Baltimore, USA), a member of Magnum Photos since 1976, became known for her work in the conflict zones of Central America (1978–1983), and in particular for her powerful photographs of the Nicaraguan revolution. Endlessly exploring and developing narratives, she involves her subjects in her works, often working over long time spans and covering a wide range of subjects and countries, from war to human rights issues and cultural identity to the sex industry. This exhibition, entitled Mediations after an eponymous work, is the most comprehensive retrospective ever held in Europe, bringing together a selection of works from the 1970s to the present day. Mediations (1978–1982) is based on Meiselas’s initial experience during the popular insurrection in Nicaragua. The selection process of her images for the publication Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 and the use of the same photographs by the mass media left her with many questions about how images are used in different contexts. Towards the end of the 1990s, Meiselas started to use archival material that she collected, published and exhibited as part of multimedia installations, thereby giving a voice to individuals and communities subject to violence and oppression.

Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona October 11, 2017 – January 14, 2018

Jeu de Paume, Paris February 6 – May 20, 2018

SFMOMA, San Francisco July 21 - October 21, 2018

Instituto Moreira Salles, Sao Paulo, October 15, 2019 - February 3, 2020______________________________________________________________________

(All images © Jeu de Paume, photo Raphaël Chipault, © Fundació Antoni Tàpies, photo Roberto Ruiz, © SFMOMA, photo Katherine Du Tiel, © Instituto Moreira Salles, photo Renato Parada)

Meiselas often adopts different approaches to extend her work in various forms: photographic essays, installations, books or films. For example, the documents used in the book Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (1997) became an online archive of collective memory, akaKURDISTAN (1998), which is currently shown as an on-going project in the form of a “Storymap” created by contributors from the global Kurdish diaspora. Working as an editor, she initiated two collaborative projects highlighting the work of regional photographers – El Salvador: The Work of Thirty Photographers (1983) and Chile from Within (1991). The latter focused on work by photographers living under the Pinochet regime. Meiselas has also worked on four films on Nicaragua: she co-directed Living at Risk: The Story of a Nicaraguan Family (1985), Pictures from a Revolution (1991) and Reframing History (2004), and contributed to Voyages (1985).

This exhibition reveals Meiselas’s unique approach as a photographer who has constantly questioned the status of her images in relation to the context in which they are perceived, showing how she moves through different scales of time and conflict, ranging from the personal to the geopolitical dimension.

Carles Guerra and Pia Viewing

Exhibition curatorsEarly Works

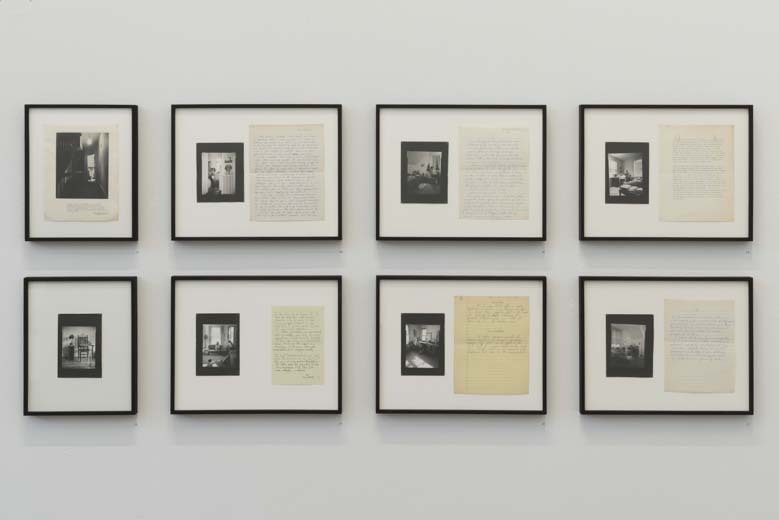

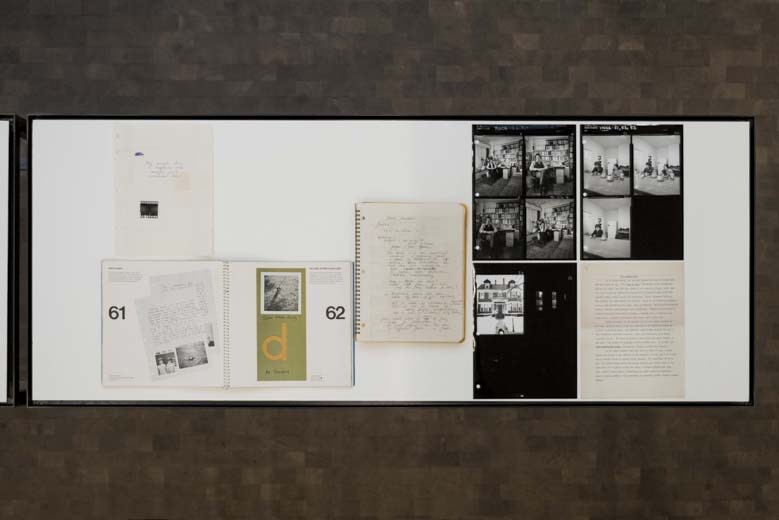

Susan Meiselas started out in photography by exploring her own immediate surroundings. 44 Irving Street (1971) is a series of photographs of her neighbors in a boarding house where she lived when she was a graduate student. Each image shows a tenant in a corner of his or her room. Some of the photographs are exhibited with a short text written by the person portrayed. The short narrative reveals how they perceived themselves in these photographs. Meiselas interacts with her subjects to explore, through her images, their relationship to place.In the Porch Portraits (1974) series, Meiselas explored an area in South Carolina where she taught photography in an elementary school. Stepping across the invisible boundary between the road and the private properties, she took portraits of the people in front of their small wooden houses with open verandas.

Following this experience, she developed a community-based project in Lando, an old company‑owned mill town, to portray its multi-generational life through a “visual genealogy” of families living there. This project, the first in which Meiselas compiled an archive with the participation of a community, includes images from family albums and portraits of the inhabitants.

Prince Street Girls (1975–1990) was shot over a period of 15 years in Little Italy, New York, a neighborhood where Meiselas still lives. The young girls (aged 8 to 10 years in 1975) used to hang out on the streets and initially they became a subject of her attention by chance. The photographs show the gradual transformation of their lives and bodies, as they become young women.

Central America

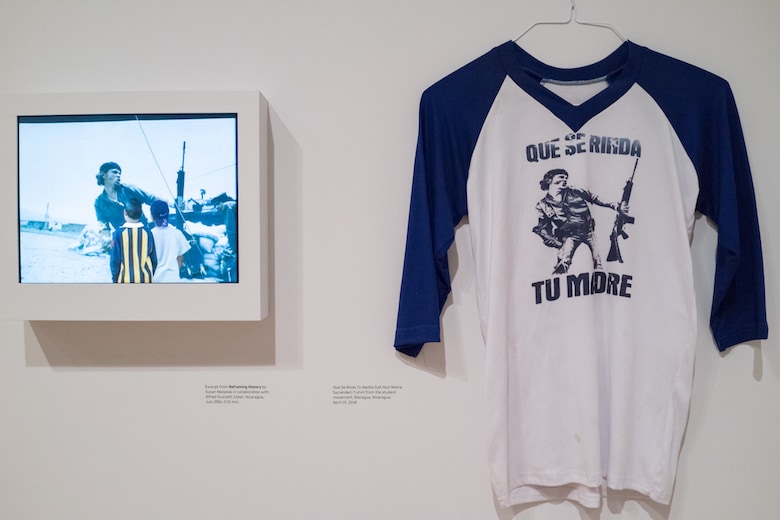

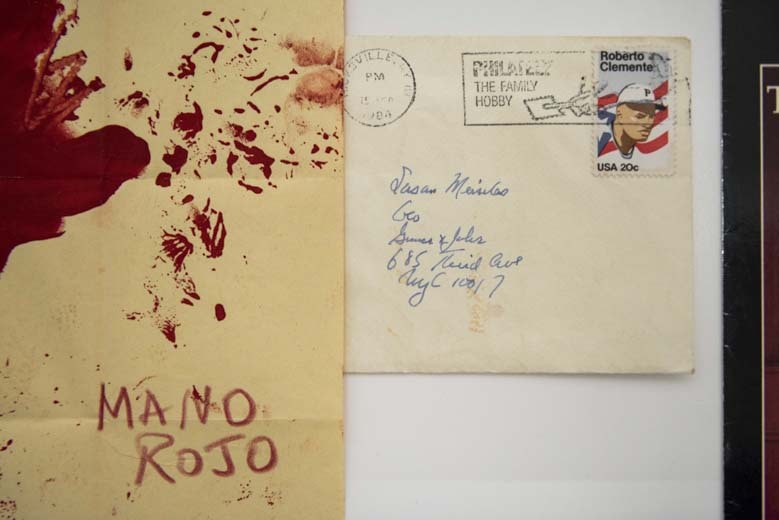

The heart of this exhibition is made up of works in which the artist questions the use of the photographic image. Without an assignment of any sort, Meiselas went to Nicaragua to cover the popular insurrection following the assassination of the editor of the opposition newspaper La Prensa. “I am not a war photographer in the sense that I didn’t go there for that purpose,” explained Meiselas. “I’m really interested in how things come about and not just in the surface of what it is.” Over three decades, in times of war and peace, Meiselas returned to the sites where she took the original photographs, using her book Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 (first edition 1981) to find the people she had photographed and record their testimonies, resulting in her third film on Nicaragua, Pictures from a Revolution (1991).The installations Mediations (1978–1982) and The Life of an Image: Molotov Man (1979–2009) retrace the history of the images she took and the contexts in which they have been published or reappropriated. Some of them became icons of the Nicaraguan revolution. In 2004, she installed large murals of photographs taken during the revolution in the very places where she had captured everyday life during the turmoil. This was a way of questioning the value of the images over time by triggering collective memory. This specific on-site process formed the central theme of the film Reframing History (2004).

The El Salvador series (1978–1983) captures the violence of the military dictatorship and the civil war that followed the coup d’état of 1979. It portrays life continuing near the sites of such killings, revealing the on-going tension between the military and the civilian population.

Kurdistan

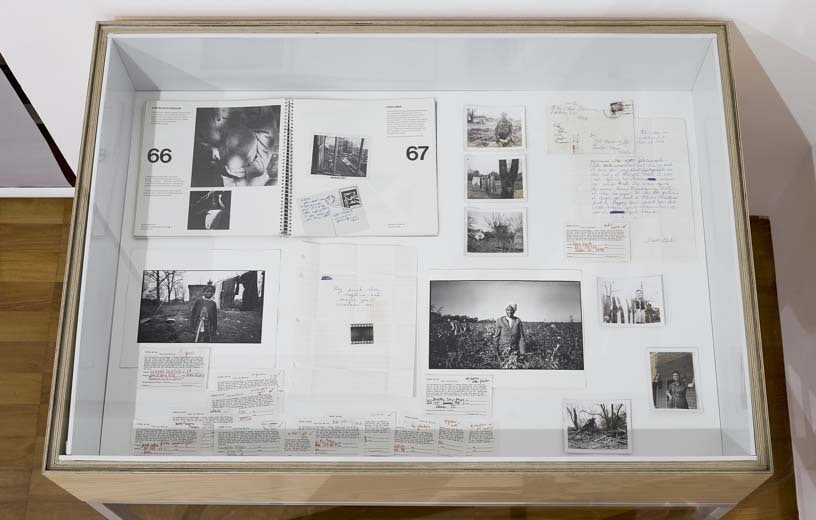

Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (1991–2007) is a multimedia project comprising photographs, videos, documents and oral accounts collected by the artist. This archive of collective memory reveals the history of a people dispersed throughout the world. Meiselas originally arrived in northern Iraq to document Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaign of genocide against the Kurds launched in 1988. She felt that contemporary photographs could bear witness to a crime by imaging the exhumation of a mass grave of individual remains. The victims, however, were Kurdish citizens from civil society who could only be portrayed through the past century of images that revealed their aspirations for a Kurdish homeland.

Meiselas explains her interest in the images and documents that she compiled to make this work: “I became preoccupied by the idea that ‘pictures are made and taken away’, so a culture might not get to see itself. There is also the issue of what happens after an image is made. I began to backtrack to Western archives and family collections to discover where a photograph of a Kurd might be – out in the world, lost, buried in a depository. Then I felt an additional sense of responsibility to repatriate what I had found. The burial released the metaphor for uncovering Kurdistan, which lives in the act of digging. The digging unleashed an obsessive gene that drove me to search for what had gone missing, and what remained unknown. The trawling through the archives was parallel with the witnessing and the actual exhumation of graves.”

The installation includes a “Storymap”, to which the accounts from a diaspora Kurdish community are regularly added (through participatory workshops), making each exhibition site-specific.

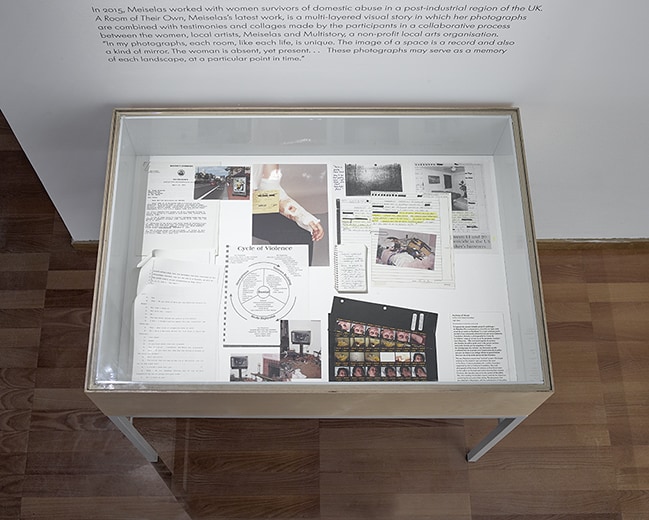

Domestic Violence

In 1992, Meiselas was asked to contribute to an awareness campaign to give greater prominence to growing domestic violence in San Francisco. This led her to create Archives of Abuse, collages of police reports and photographs of crime scenes, exhibited in the city’s public spaces as bus shelter posters. “My instinct”, said Meiselas, “was to start with the evidence – sometimes found in hotel rooms, sometimes in homes. . . . I recognised the power of absence within these archives of abuse. I imagined the places where things had happened, and discovered the emptiness of the aftermath image. A scar or wound is evidence, but the place itself is only really known to the person on whom the violence was inflicted. It exists in memory.”In 2015, Meiselas worked with women survivors of domestic abuse in a post-industrial region of the UK. A Room of Their Own, Meiselas’s latest work, is a multi-layered visual story in which her photographs are combined with testimonies and collages made by the participants in a collaborative process between the women, local artists, Meiselas and Multistory, a non-profit local arts organisation. “In my photographs, each room, like each life, is unique. The image of a space is a record and also a kind of mirror. The woman is absent, yet present. . . . These photographs may serve as a memory of each landscape, at a particular point in time.”

'Emergency Room,' one of five multi-media pieces as part of A Room of Their Own

The Sex Industry

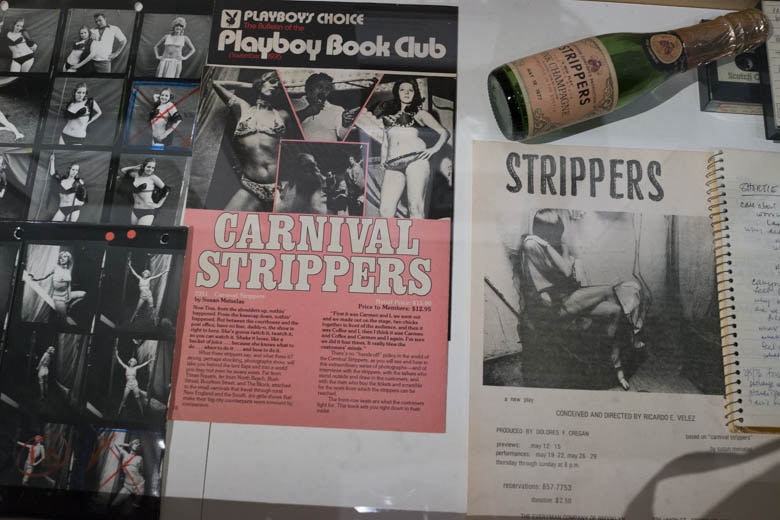

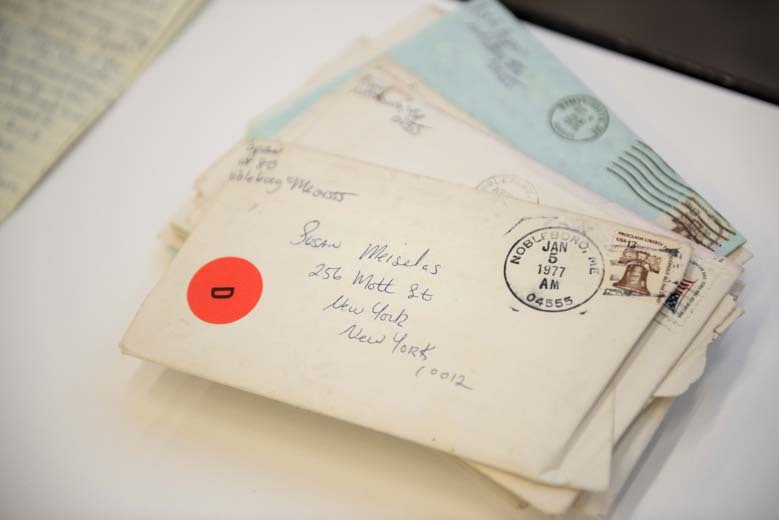

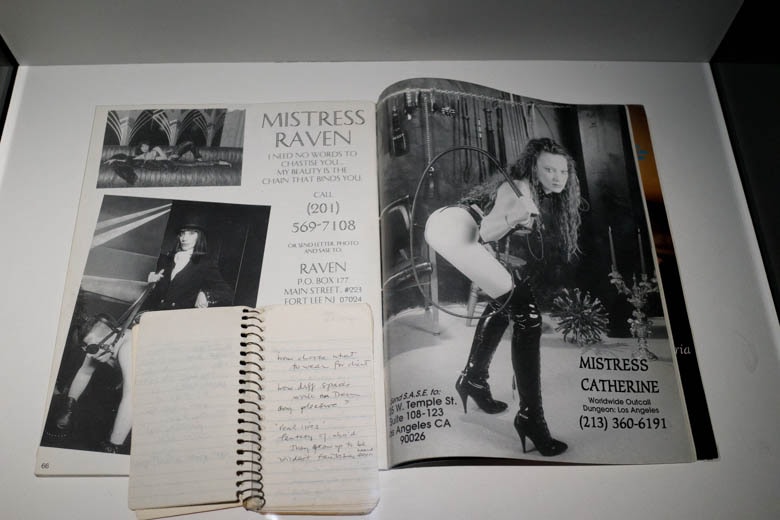

Meiselas followed strippers working in carnivals in New England over the course of three consecutive summers. Carnival Strippers (1972–1975) is an installation comprising her first major photographic essay and audio recordings of the women, their clients and managers. With a small Leica and no flash, she concentrat-ed on the working lives and the power dynamics of the “girl shows”, portraying them with multiple perspec-tives, through reportage and portraiture. Meiselas describes her approach to this project as being influenced by her ethnographic studies: “I wanted to see the whole world of the carnival strippers from within, as well as looking out. . . . Feminists at that time perceived the girl shows as exploitative places and thought the women were victims. But I was more interested in seeing how they were seen within their world, and hearing what the women said about themselves rather than what other people said about them. I was drawn to know what motivated them.”Her Pandora’s Box series (1995) was taken in an S&M club in New York and, to a certain degree, it can be thought of as a sequel to Carnival Strippers. She linked the images to the testimonies of the people involved: the manager, the mistresses and the clients. In this small place, she discovered yet another relationship to pain and violence focusing on controlled acts of violence producing self-inflicted pain: “At Pandora’s Box I was witnessing an individual choose to participate in what looked from the outside like a violent act. But it represented play in a controlled setting where the man could say, ‘Mercy, mistress’, and it stopped. Still, I found that challenging. And as with Carnival Strippers, it was the power relations that really captured my attention – women who wield a kind of power that is suspect to others.”

20 dirhams or 1 photo?

Though the relationship between photographer and subject has always been central to Meiselas’s work, it was the explicit focus of a commission she completed for an exhibition in Morocco, in 2013. Working on a short timeline and in an unfamiliar culture, Meiselas faced a further challenge: the people of Marrakech did not want to be photographed. With two young Moroccan women as her assistants, Meiselas interviewed women in the spice market and learned that this was not due to modesty or religious custom, as she had assumed. They simply wanted to be paid.

Meiselas took this opportunity to open a dialogue about the value of imagery, in both monetary and symbolic terms. She set up a pop-up studio in the market and invited women working nearby to come have their pictures taken. Each participant could keep her portrait or be paid twenty dirhams—the average price of an ID photo—for allowing Meiselas to use it in the exhibition. By choosing an amount associated with a routine purchase, the artist shifted the significance of the exchange from a question of financial gain to one of agency. Sixty women opted to be paid, while eighteen chose to keep their portraits. In their place Meiselas exhibited twenty-dirham notes, as a symbol of their encounter. When Meiselas made additional copies of the installation, such as this one, she increased the sitters’ compensation to 50 dirhams.

Corey Keller

Curator of Photography, SFMOMA, 2018