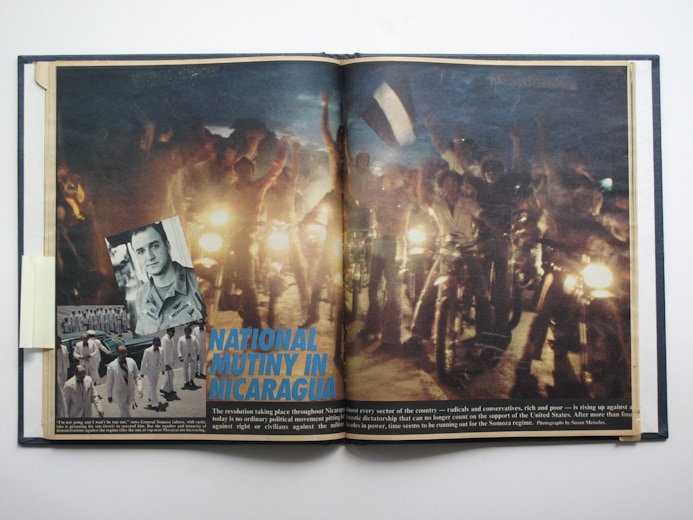

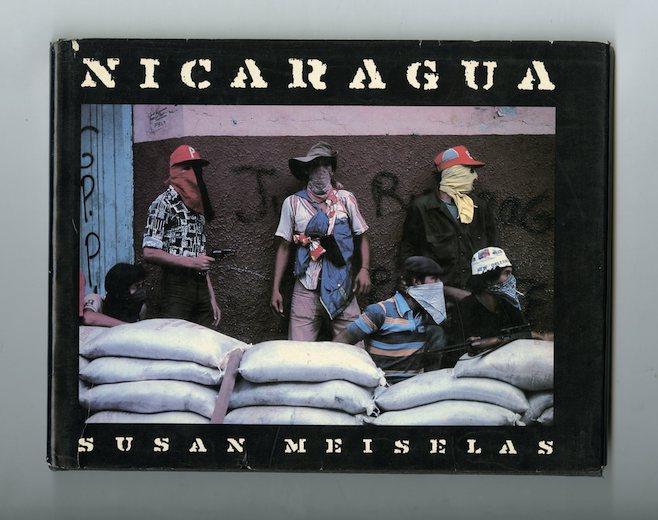

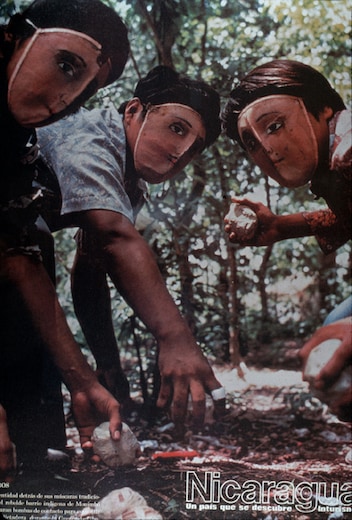

Nicaragua 1978 - 2004

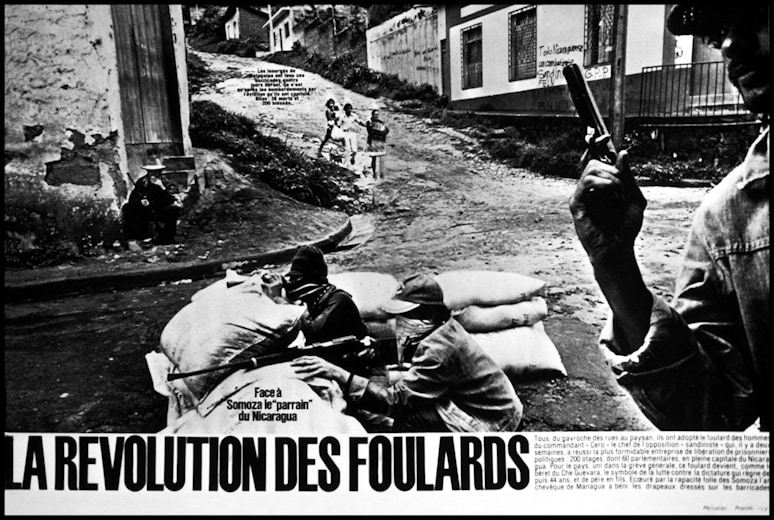

1978-1979

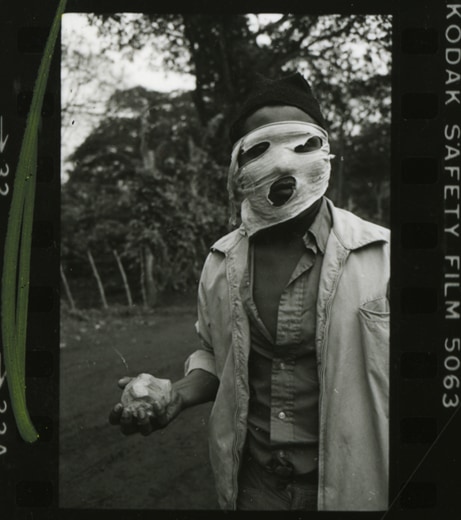

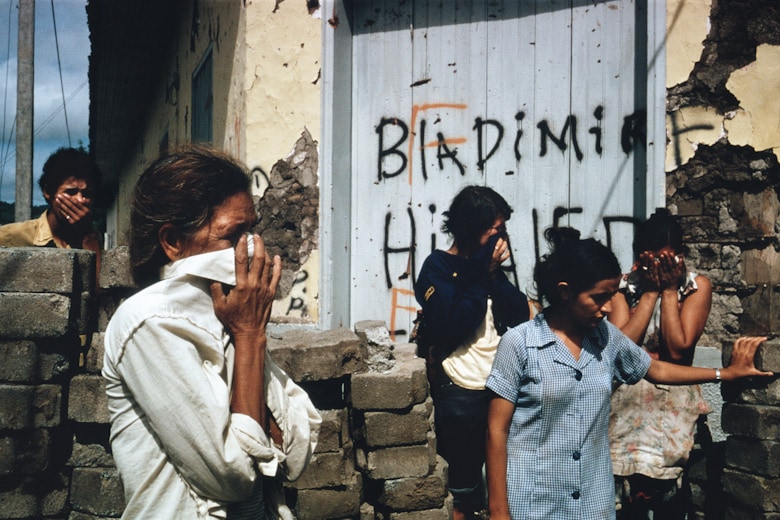

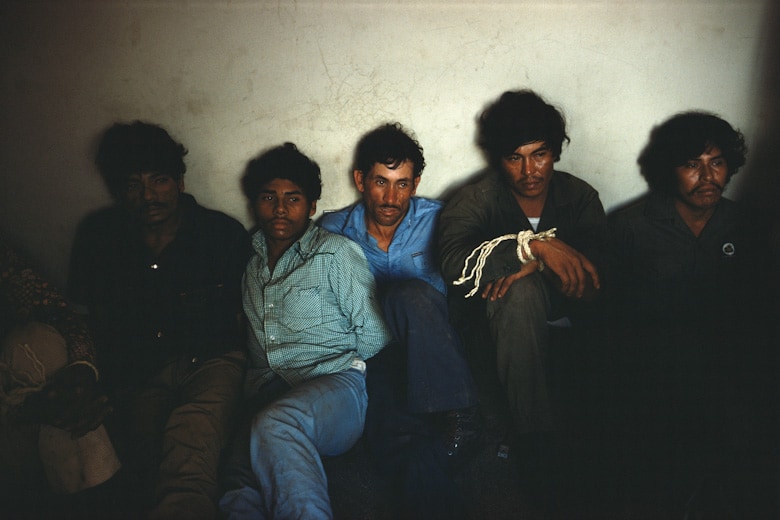

When I went it was quite a strange experience. The general impression I had from Nicaragua was that everybody was waiting for something. And it was waiting for something that they were going to do. Increasingly I felt that the kind of pictures I was taking gave maybe a small clue as to the texture of their lives, but very little.

I spent six weeks there principally, because all I could feel was that I wasn’t doing anything that gave a feeling for what in fact was going on there. Not going on in the world of events, but going on in terms of how people were feeling. And that still plagues me because I am not a war photographer in the sense that I didn’t go there for that purpose. I’m really interested in how things come about and not just in the surface of what it is. -S.M.

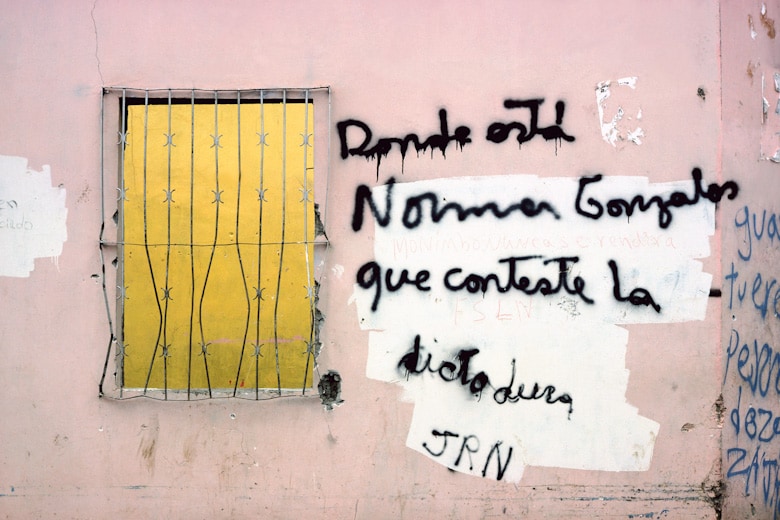

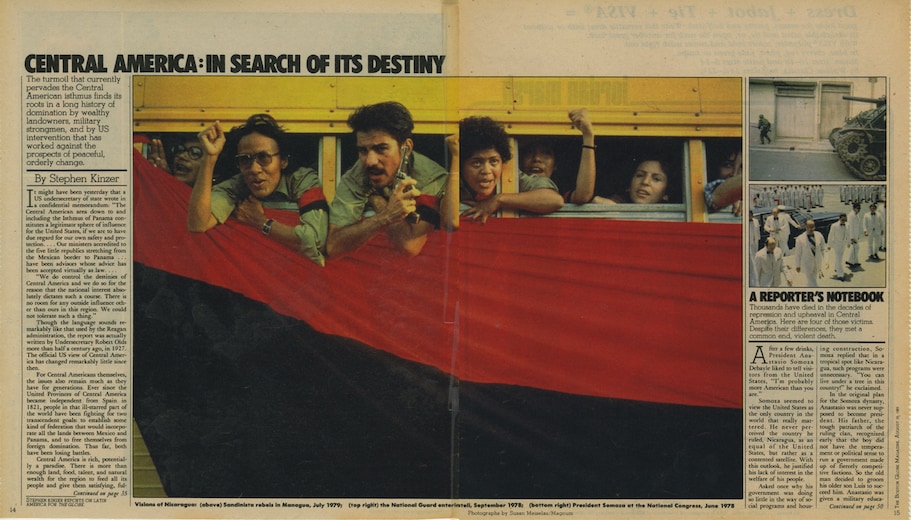

"No me voy ni me van...I'll neither go nor be driven out."

- General Anastasio Somoza Debayle, 1978

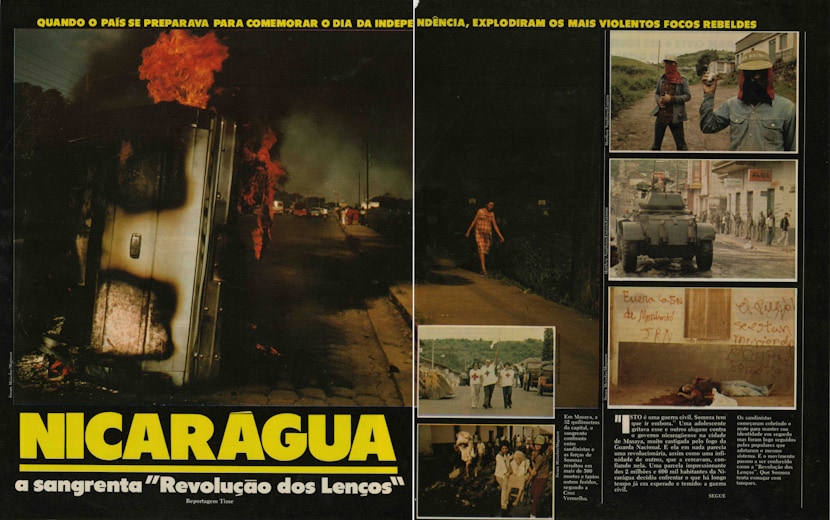

Nicaragua in 1971

Population: 2.2 million

Government: Ruled by the Somoza family since 1936

Land: 5% of population owned 58% of arable land; Somoza family owned 23%

Wealth: 50% of population had an average annual income of $90

Housing: 80% without running water, 59% without electricity, 47% without sanitary facilities, 69% with dirt floors

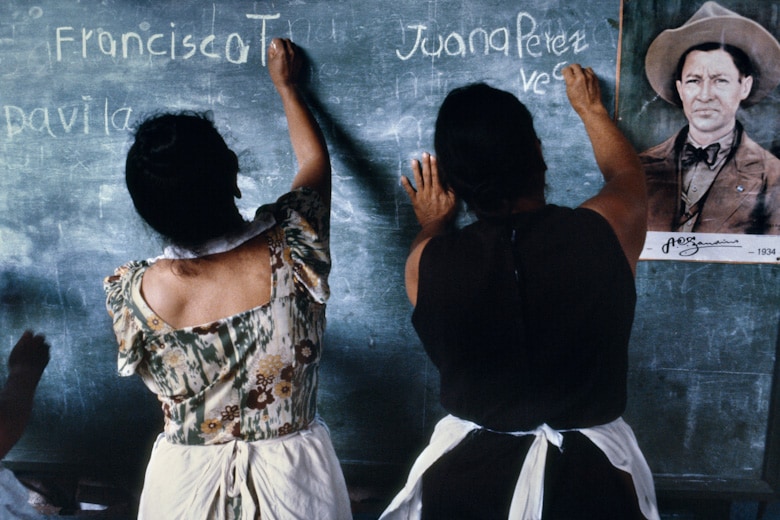

Illiteracy: 57% nationwide, but 80% average in rural areas

Health: Endemic malaria, tuberculosis, typhoid, and gastroenteritis. Of every 1,000 children born, 102 died. Of every 10 deaths, 6 were caused by infectious diseases, which are curable.

"An unarmed people's war is nothing like a military coup. It is a war of attrition, long and silent. Many have fallen. Thousands of its actions remain unknown. The news tells only of those that are most important. This is not something that started with these last offensives. We who live this struggle know that day by day there are confrontations, something happens. It is a long history, like building a house, stone by stone..."

–German Pomares, FSLN Commander. Died in combat May 28, 1979, in Jinotega.

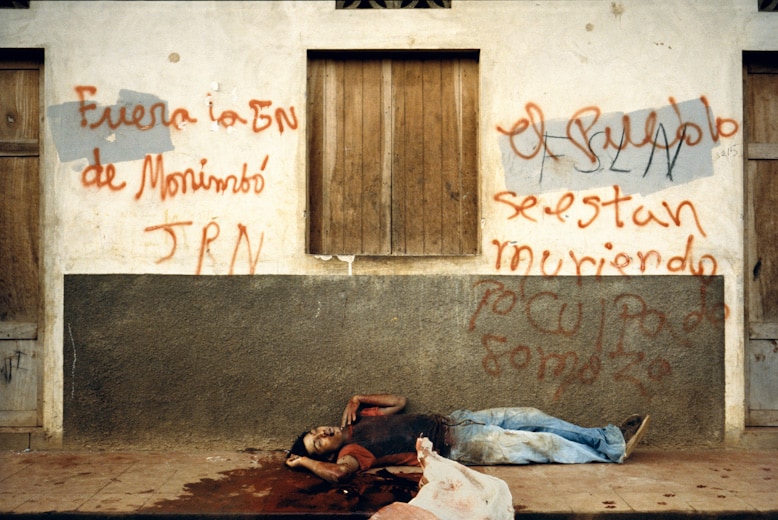

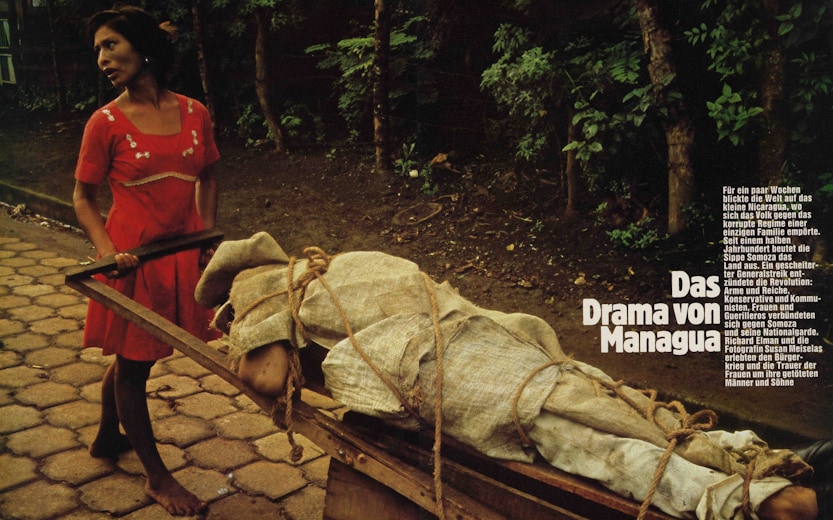

I used to get in the car as early in the morning as I could and just drive, looking for things that seemed unusual. One day I was driving on the outskirts of Managua when I smelled something. It was a very steep hill, and as I got closer to the top the odor overwhelmed me. I looked out and saw a body and stopped to photograph it. I don't know how long it had been there, but long enough for the vultures to have eaten half of it. I shot two frames, I think, one in color and one in black and white, then got out.

The images I made of the body were powerful partly because of the contrast with the beauty of the landscape. For me [the photo] was the link to understanding why the people of Nicaragua were so outraged. [On the other hand] the American public could not relate their reality to this image. They simply could not account for what they saw. -S.M. from "Exposure 21," no.1 (1988)

"Dear Parents: I’m sure you’ve noticed my odd behavior over the past months. I no longer go to parties. I appear and disappear. This is because I’ve become a revolutionary, a member of the FSLN. I’ve done this for the following reasons: For twenty years I have lived as I pleased and spent wildly while thousands of children, the sons of peasants and workers, suffered hunger, and died of malnutrition or in need of medical care. Our country is full of misery and backwardness. All Nicaraguans have the sacred mission to fight for the freedom of our people. Our generation is doing what past generations should have done. Injustice and crime reign in the enslaved Nicaragua you have left us. We do not want our children to accuse us of the same thing. The stench of the Somoza regime has become unbearable to the young. If our parents learned to live with this rotten government, we are prepared to risk our lives to put an end to it. I am going to the mountains, where the patriots, the honest human beings, those who are willing to sacrifice everything for their people, can be found."

–Excerpt from a letter written by Edgard Lang Sacasa to his parents. His father, Federico Lang, was a wealthy Nicaraguan businessman and supporter of Somoza. Edgard was killed by the National Guard on April 16, 1979.

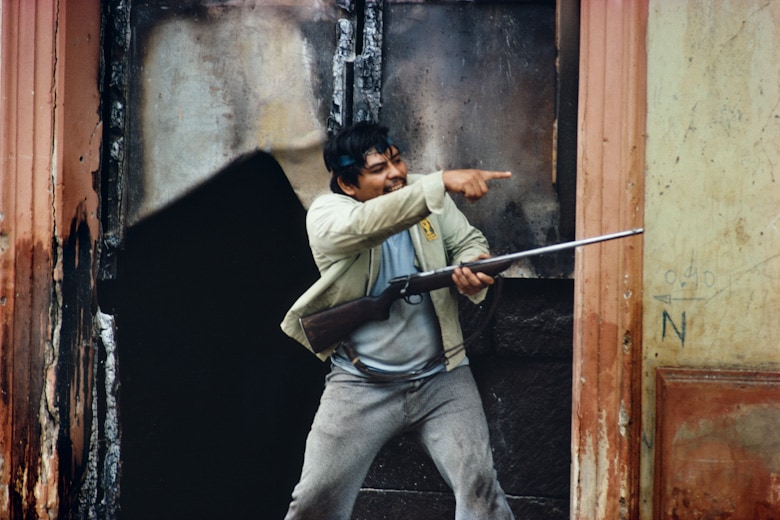

One day, after a shooting in Jinotepe, some students carried around the portrait of a young woman named Arlen Siu who had been killed months before in the mountains. At one point, as they charged down the street chanting, someone confronted me with a bullet made in the U.S.A. and asked me what I was doing there, and which side I was on. It went beyond the question of "Why am I taking photographs?" or "Who am I taking pictures for?" It was a pivotal moment. It gradually became clear to me that as an American, I had a responsibility to know what the U.S. was doing in other countries. -S.M. from "In History"

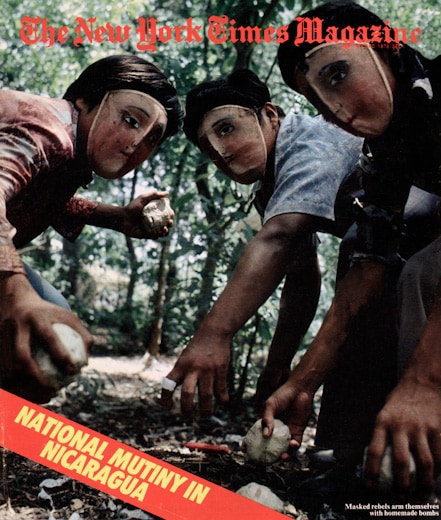

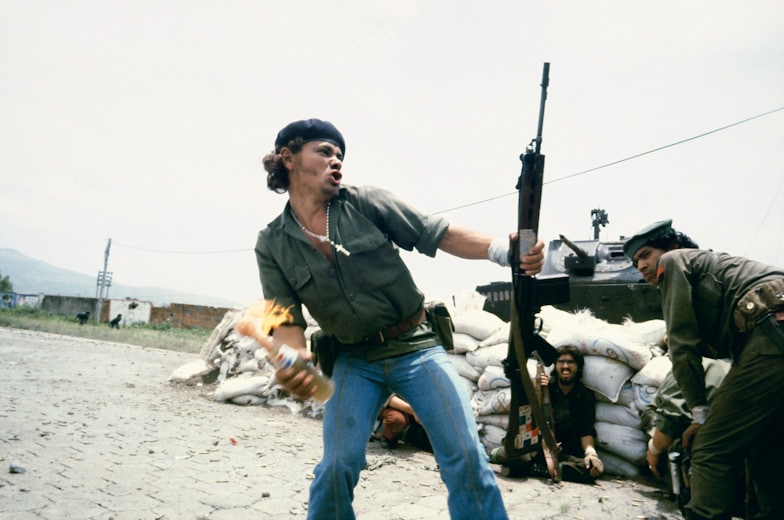

...At the time, I wasn't taking a position in the debate about whether war should or shouldn't be shown only in black and white...I initially worked with two cameras, one in black and white and the other in color, but increasingly came to feel that color did a better job of capturing what I was seeing. The vibrancy and optimism of the resistance, as well as the physical feel of the place, came through better in color. -S.M. from "In History"

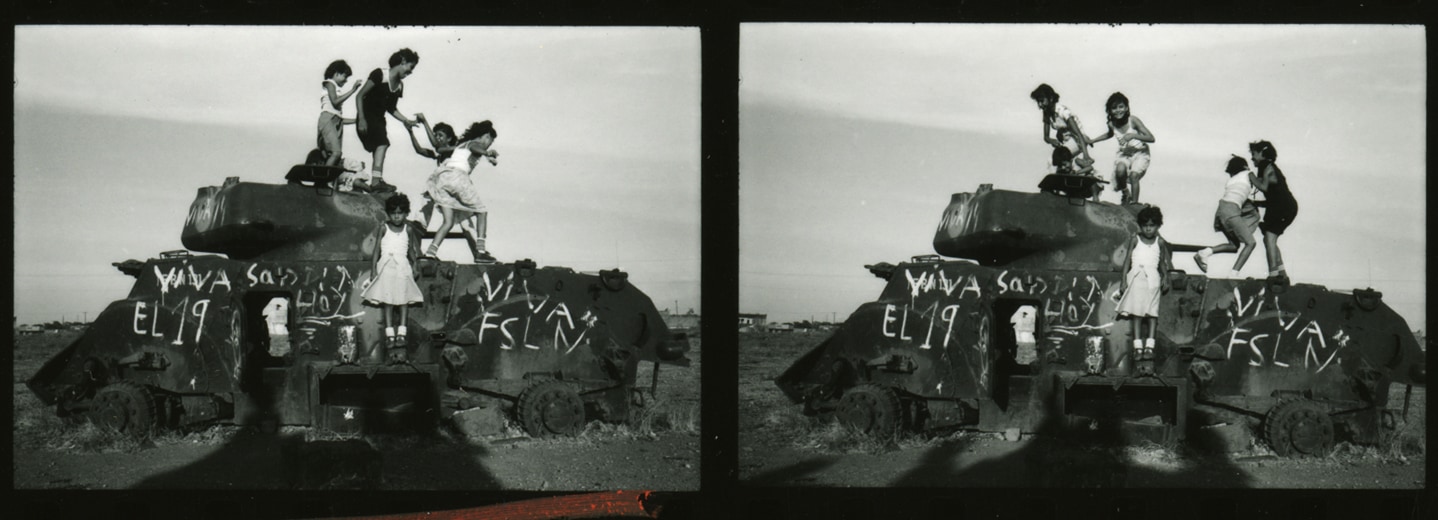

“History doesn’t come to an end with the ringing of the bells by the grave, or with the rumbling of tanks against a peaceful city. History begins when it is firmly established that an ideal lives in a people, though men die...”

–Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, editor of the opposition newspaper La Prensa. Assassinated January 10, 1978.

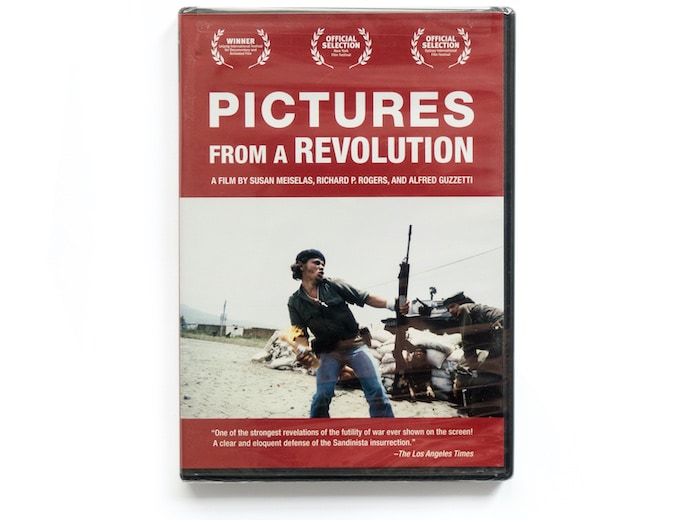

Ten years after the insurrection, Susan returned to Nicaragua with filmmakers Richard Rogers and Alfred Guzzetti to discover what happened to the people pictured in her book. This clip and the excerpts that follow are from the film, Pictures From a Revolution.

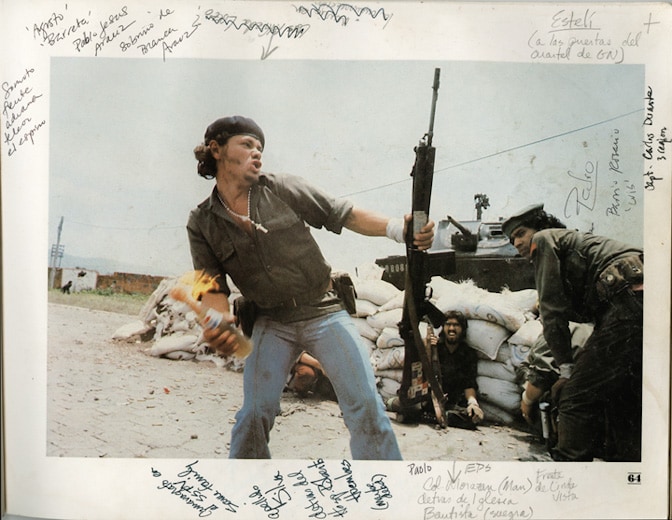

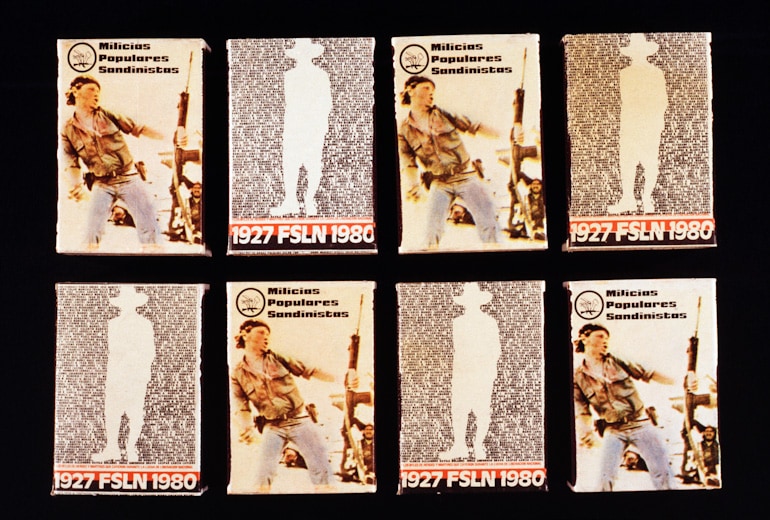

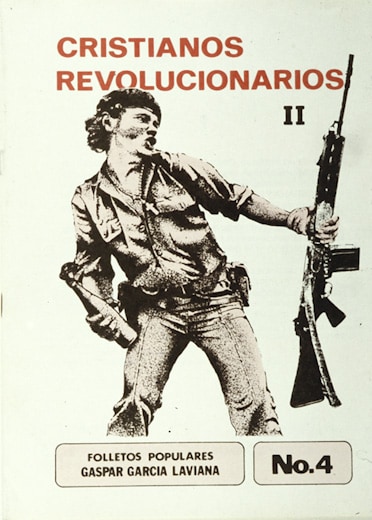

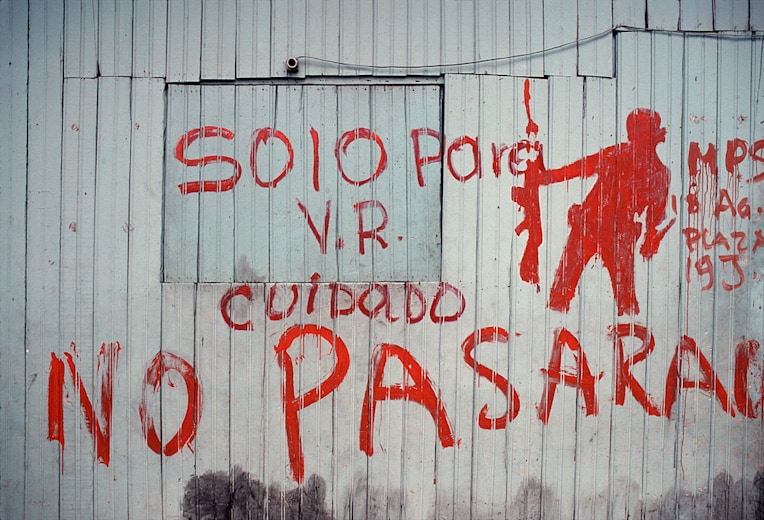

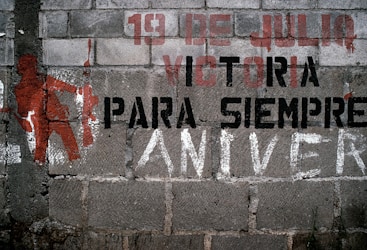

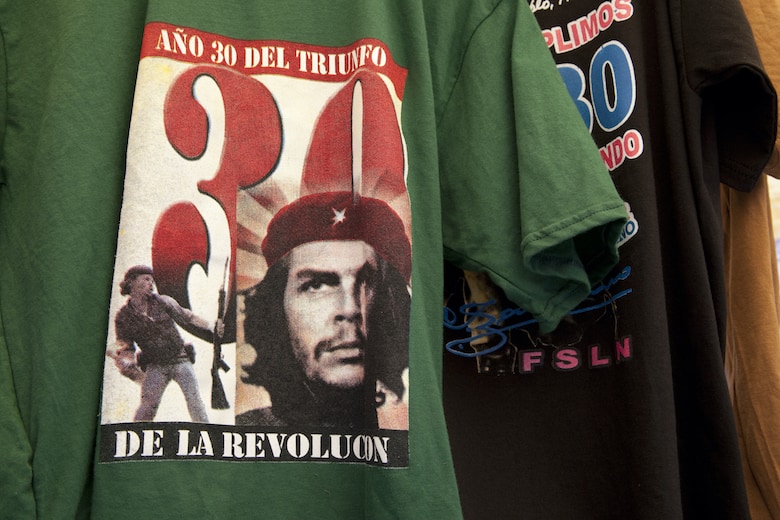

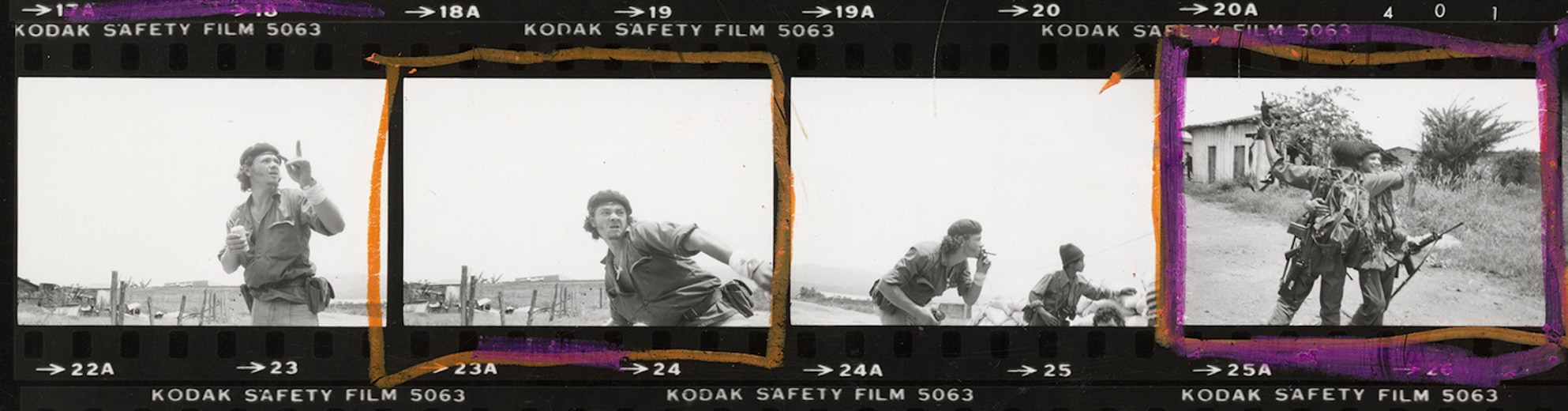

On the day before Somoza would flee Nicaragua forever in July of 1979, Susan photographed the Sandinista Pablo 'Bareta' Arauz throwing a molotov cocktail at one of the last remaining Somoza National Guard regiments remaining under the dictator's control. During the months and years that followed, the image evolved into a symbol of the Nicaraguan revolution. Murals and graffiti of the "Molotov Man" could be seen all over the country. It appeared in a matchbook commemorating the one year anniversary of the Sandinista revolution, on t-shirts, brochures and advertisements. Twenty-five years later, Bareta's likeness was adopted as the "official" symbol of the Sandinista overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship.

"For me it is strange, I am in fact famous for that reason perhaps not only in Nicaragua but internationally and I feel calm, happy. In fact, always I have stayed on the margin of the revolution. After the triumph of the Sandinista Front, I always participated in the tasks of the revolution. I voted for the Sandinista Front. And I am Sandinista, independently of the fact that the Sandinista Front lost in free and civic elections. But I continue being Sandinista regardless of the regime that might still come. My conscience is Sandinista until my death."

–Pablo 'Bareta' Arauz, 1990. Interview outtake from Pictures From a Revolution.