El Salvador

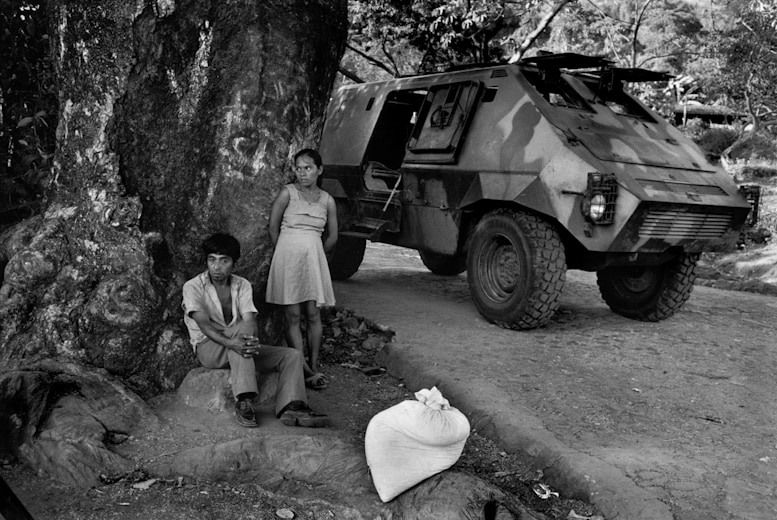

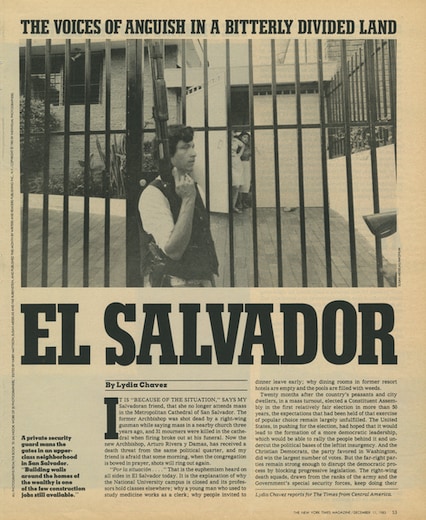

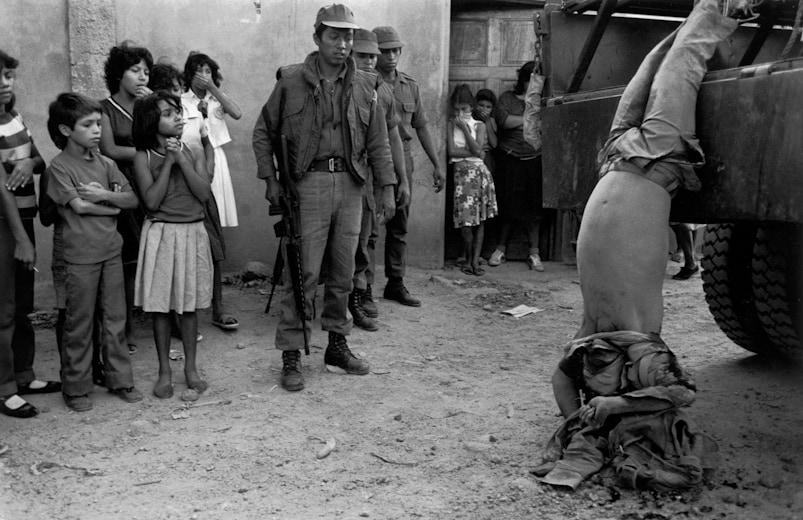

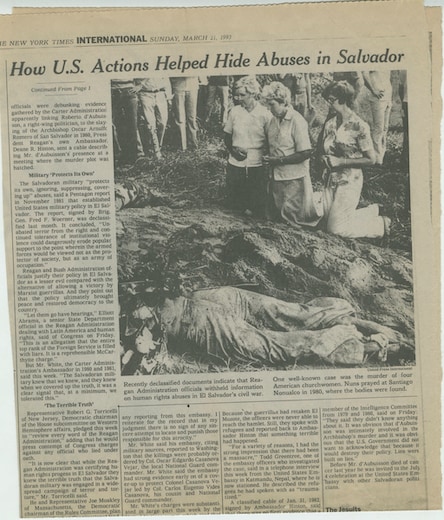

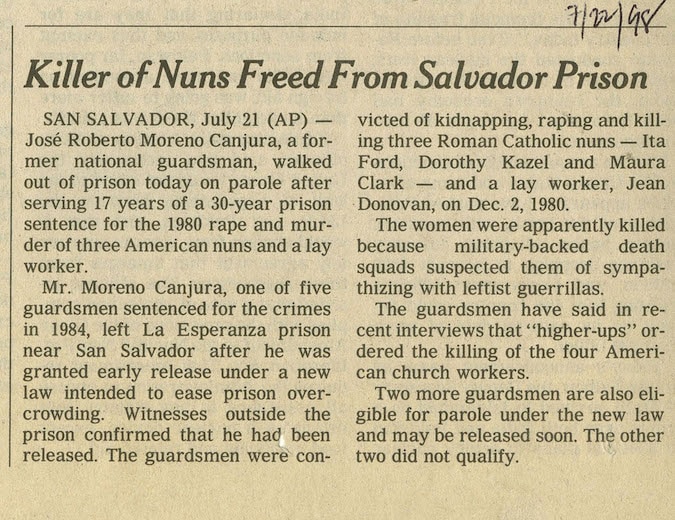

Following years of repression under military dictatorship, a coup d'etat in El Salvador in 1979 sparked a brutal, twelve-year civil war. The subsequent assassination of human-rights advocate Archbishop Oscar Romero and the murder of four U.S. churchwomen in 1980 drew world attention to the political oppression and violence in that tiny country.

In the U.S., the newly elected President Ronald Reagan was determined to limit what he perceived as leftist influence in Central America following the popular insurrection that overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in neighboring Nicaragua, and the administration supported the Salvadoran junta with military and economic aid throughout the 1980s.

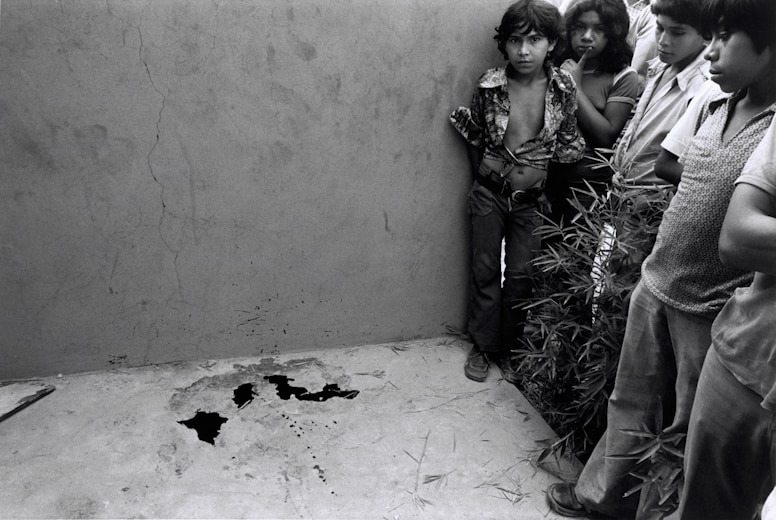

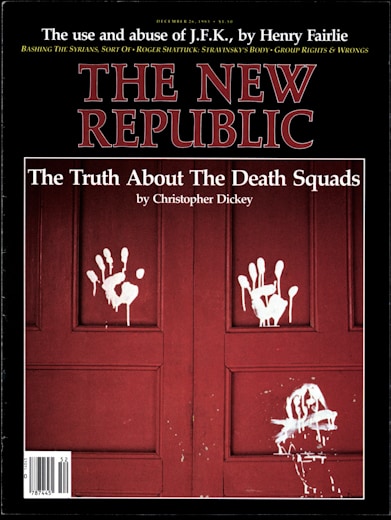

During this time, death squads associated with the military terrorized civilians, sometimes massacring hundreds of people at a time. All told, the war cost the lives of 75,000 civilian noncombatants.

-Kristen Lubben, Editor of In History, 2008

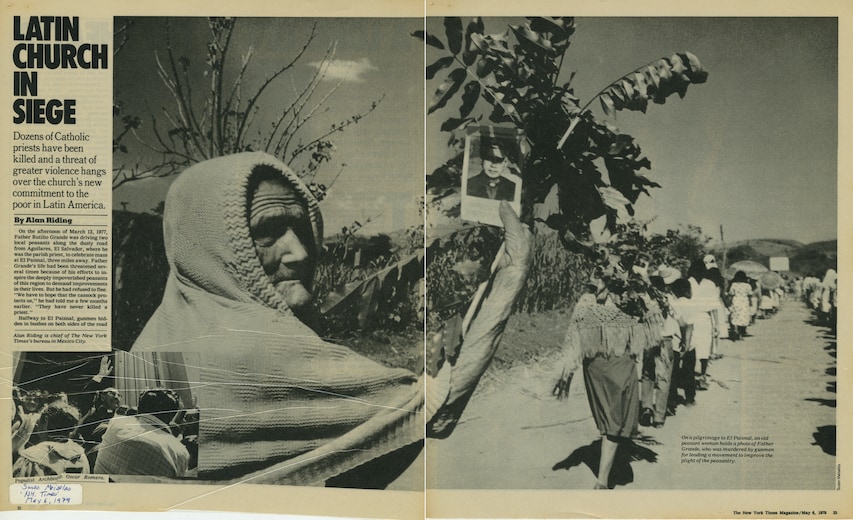

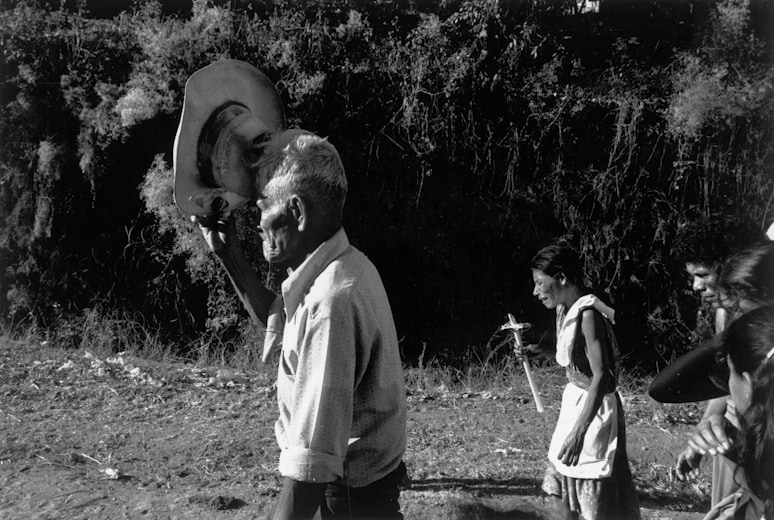

There was persecution of FECCAS (Cristian Federation of Salvadorean Peasants) and UTC (Peasants Work Union). UTC was active in Arcatao, my brother was a leader, though he was not a peasant but he fit in well. The terrorist organization Mano Blanca was organized by Gen. Medrano who was going after people from the left or fighters at that time. He painted white hands on houses where leaders or members of these organizations lived. My brother found this sign on his door.

They were saying that in San Vicente the priest was killed and that it would be like that with everyone. The white hands would warn them that they could be murdered.

I am sure that the white hands on my brothers door were painted in August 1979.En Arcatao my brother was the first one to be murdered, he was not fearful, he also chose to stay and was killed on the 14th of October 1979.

- Zoila Menjivar, Ernesto Menjivar's sister, from an interview with Susan Meiselas, December 2016

In Arcatao, too, there were outrages, made by the National Guard. They killed Ernesto Menjivar, captured Elias Pineda because they heard him mourning the death of

Mr. Menjivar. They also captured Antonio Miranda Tenquesque and Meliton Martinez and the three of them appeared dead.Again, on Tuesday another group arrived to encircle the town and to intimidate surroundings cantons; in Las Lomas they captured the young Santiago Ayala, who also was found dead. An helicopter and other military contingents were spreading fear. On Wednesday at 8pm, arbitrarily they broke into the Arcata Convent and started searching. It is not known if they respected their belongings.

- Transcription excerpt by Mgr. Oscar Arnulfo Romero where he mentioned the events in Arcata, October 21st, 1979

On the night of December 2, 1980, four women of the Maryknoll church were in a van on their way from the San Salvador airport when Salvadorean National Guardsmen stopped their vehicle. The four women -- Sister Maura Clark, Sister Ita Ford, Sister Dorothy Kazel and church worker Jean Donovan -- disappeared.

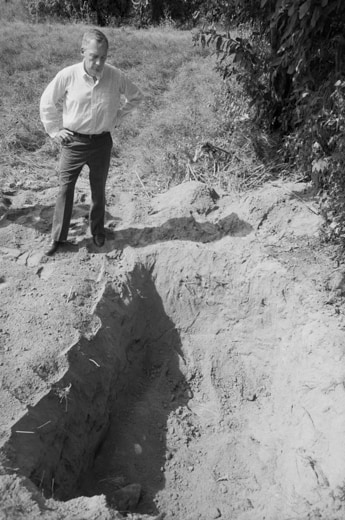

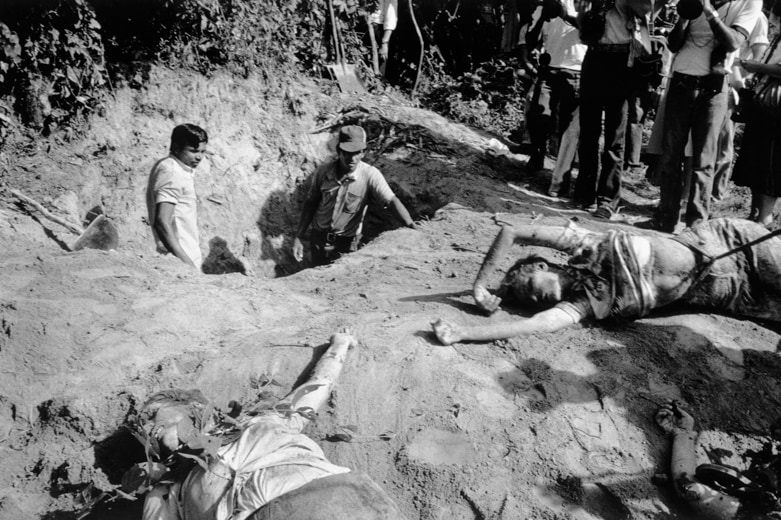

Susan and the Associated Press photographer John Hoagland were speaking with villagers in the area where the nuns disappeared when they met a peasant who described being instructed to bury the "four White women," that he found in a nearby field. On December 4, the bodies of the missing women were discovered in a field 5 miles from the nearest paved road, and 10 miles from the airport. When the bodies were exhumed, it was discovered that the four women had been brutally beaten and raped before being killed. A local judge had ordered their burial without informing the press.

When news of the Maryknoll murders became public, the U.S. goverment was pressured to investigate. Initial investigations were accused of white-washing details of the crime, and eventually the United Nations established a Truth Commission to determine who was responsible and who had been involved in the attempted cover-up. In 1984, several low-level Salvadorean National Guardsmen were convicted and two Salvadorean Generals were sued in U.S. Federal Courts by the women's families.

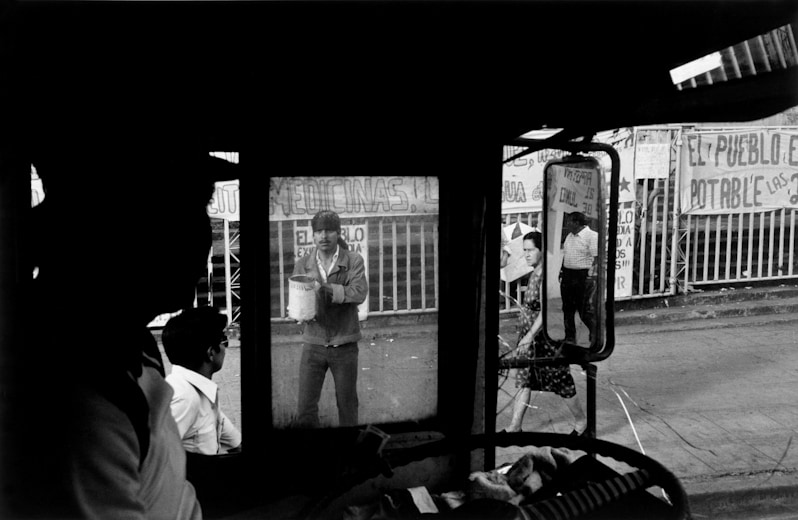

The first generation of Salvadorans suffered the somnabulism of the revolt's aftermath. Throughout the next five decades, the United States provided economic aid, military aid, and training to the Salvadoran government. High-ranking officers bought expensive homes, fine automobiles, retirement haciendas. The second and third generations awakened to the nightmare's recurrence. In the violence of hunger, despair grew volatile: in blood hosed from the plaza after fixed elections, in the arms of those who carried the dead from the streets, in the mother whose chlidren starved, in the father whose long work in the fields was never enough.

-Carolyn Forché, from El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers, 1983

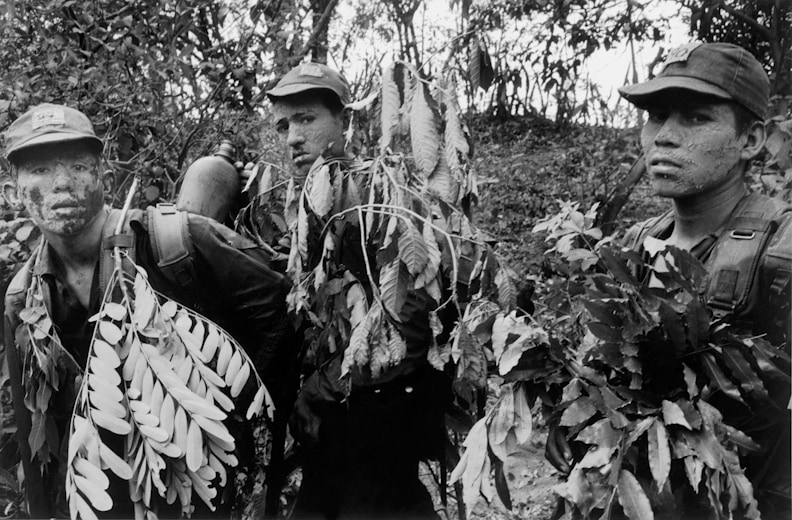

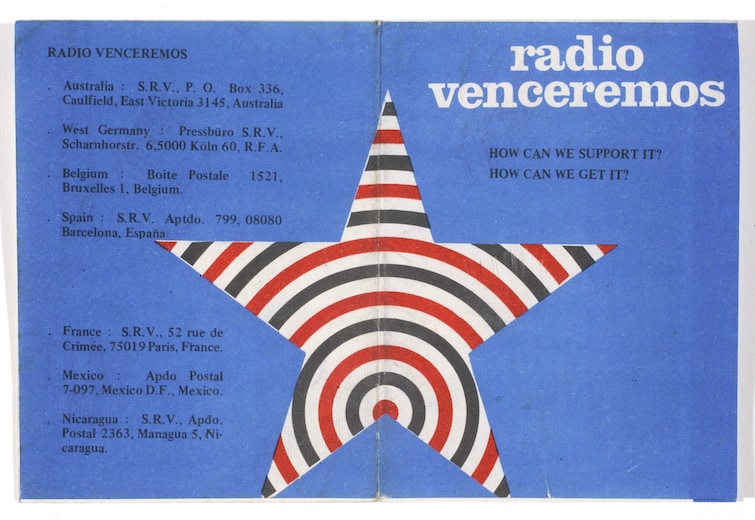

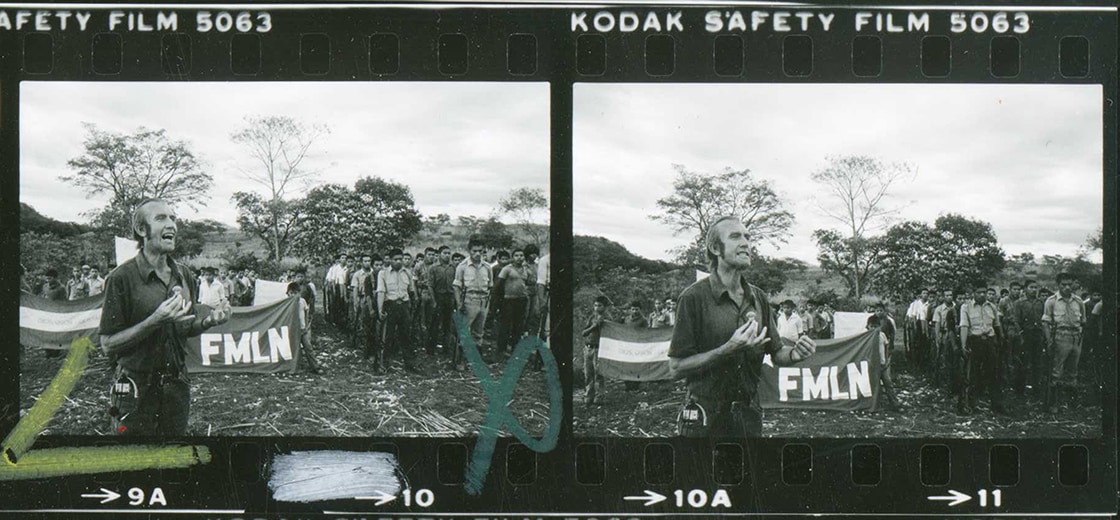

Radio Venceremos, an insurgent radio, was born simultaneously with the Farabundo Marti Front for the National Liberation (F.M.L.N.), in El Salvador, C.A., and has been transmitting without interruption from January, 1981 up to the present.

In seven years, the Front has established zones of control based upon a close relationship with the population of the rural areas. Based in one of these zones, Morazán, Radio Venceremos, official voice of the FMLN, was converted into a medium of expression for the interests and aspirations of the people.

That which was originally a clandestine radio, functions today as a source of information for the national and international press.

- Radio Venceremos flyer, date unknown

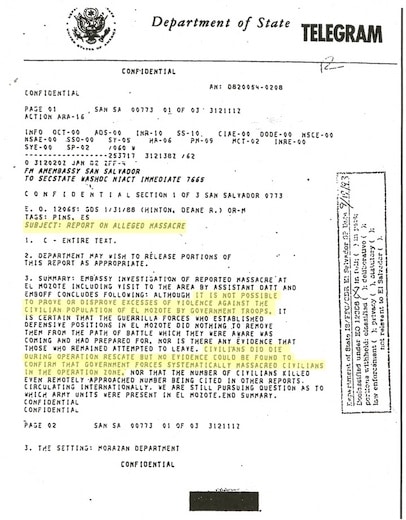

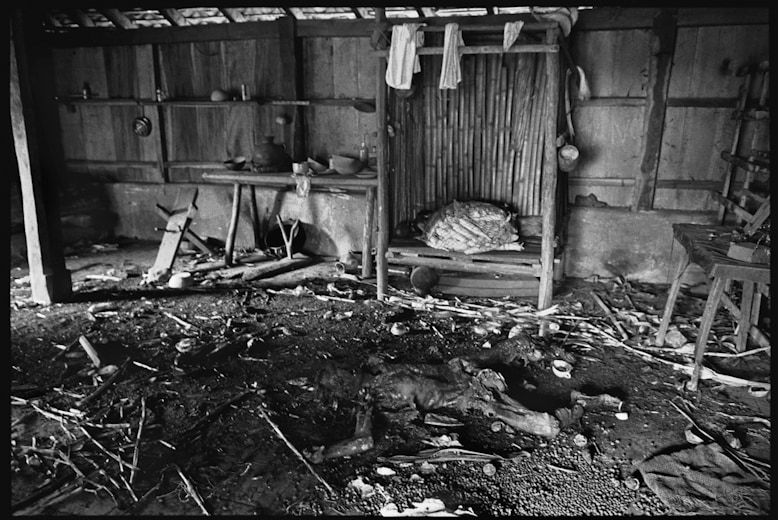

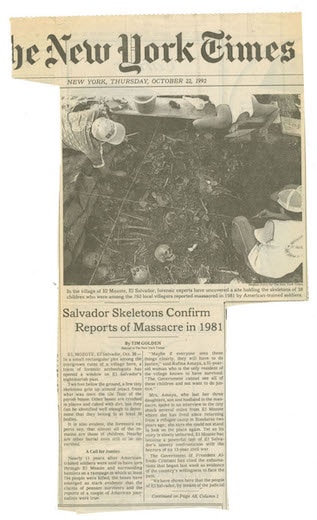

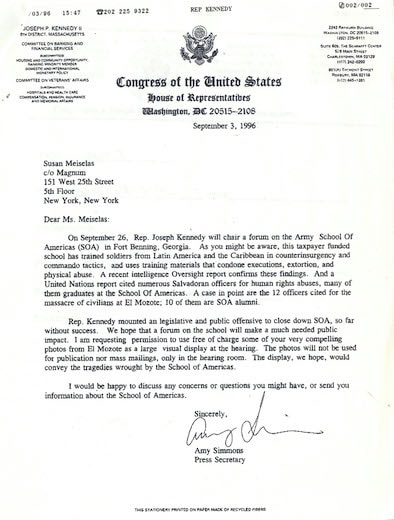

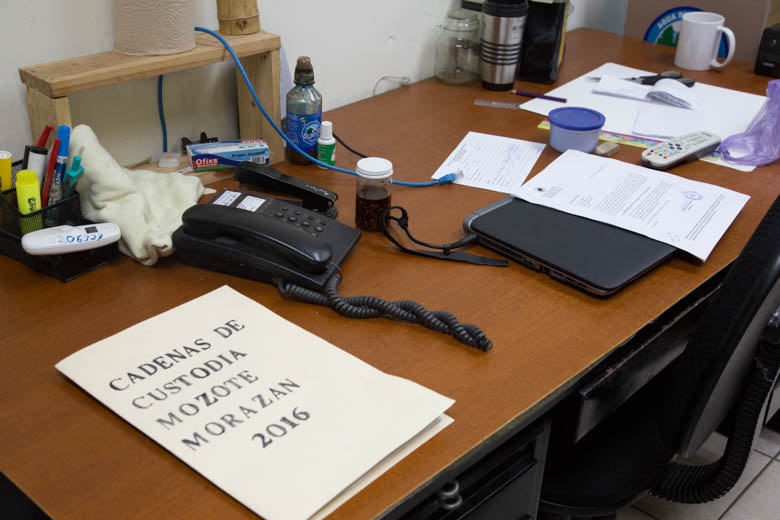

In December 1981, soldiers of the Salvadoran Army’s select, American trained Atlacatl Battalion entered the village of El Mozote, where they murdered hundreds of men, women, and children, often by decapitation. Although reports of the massacre - and photographs of its victims - appeared in the United States, the Reagan administration quickly dismissed them as propaganda. In the end, El Mozote was forgotten. The war in El Salvador continued, with American funding.

- Mark Danner from The Massacre at El Mozote, 1994

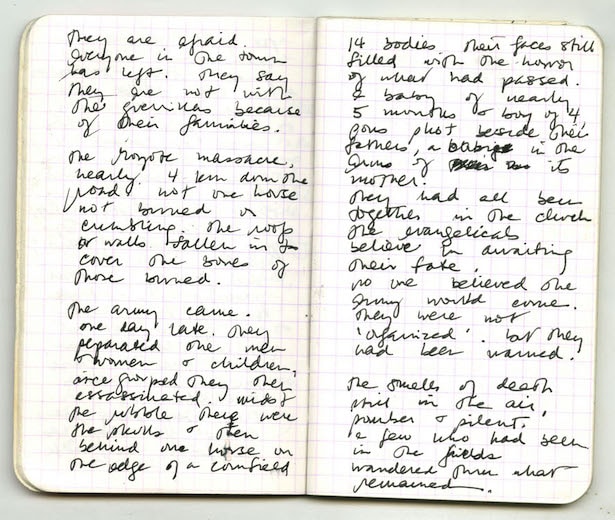

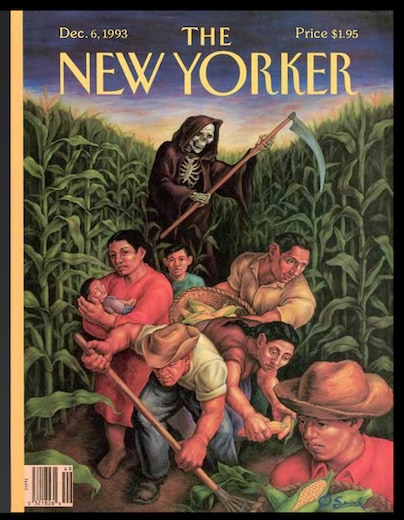

There were bodies and parts of bodies. We saw about twenty-five houses destroyed around Arambala and Mozote. My strongest memory was this grouping of evangelicals, fourteen of them, who had come together thinking their faith would protect them. They were strewn across the earth next to this cornfield, and you could see on their faces the horror of what had happened to them. - S.M.

The main challenge that we faced was that there was nothing in the place that identified what happened. During one of the meetings in preparation for the commemoration we took the decision to build a monument to give significance to the events. This action was as important as a military action because it would guarantee that the civilian massacre was true.

The only material available was iron laminate, it was a simple way to delineate a simple family structure (a man, a woman and their two kids). During the night with the help of a team to solder it was welded together.

All this effort could not be completed if the monument did not get to its destination. The monument to the victims of Mozote was erected with a wooden stick, which stood as a witness for months.

"Footprint Memory" by Fatima Argueta, January 2017

From this evidence and from a wealth of testimony, the Truth Commission would conclude that "more than 500 identified victims perished at El Mozote and in the other villages. Many other victims have not been identified." To identify them would likely require more exhumations — at other sites in El Mozote, as well as in La Joya and in the other hamlets where the killing took place. But the Truth Commission has finished its report, and, five days after the report was published, the Salvadoran legislature pushed through a blanket amnesty that would bar from prosecution those responsible for El Mozote and other atrocities of the civil war. In view of this, Judge Portillo, after allowing two American anthropologists to work in the hamlet for several weeks with inconclusive results, in effect closed down his investigation. The other victims of El Mozote will continue to lie undisturbed in the soil of Morazán.

- Mark Danner, "The Truth of El Mozote," The New Yorker, December 6, 1993

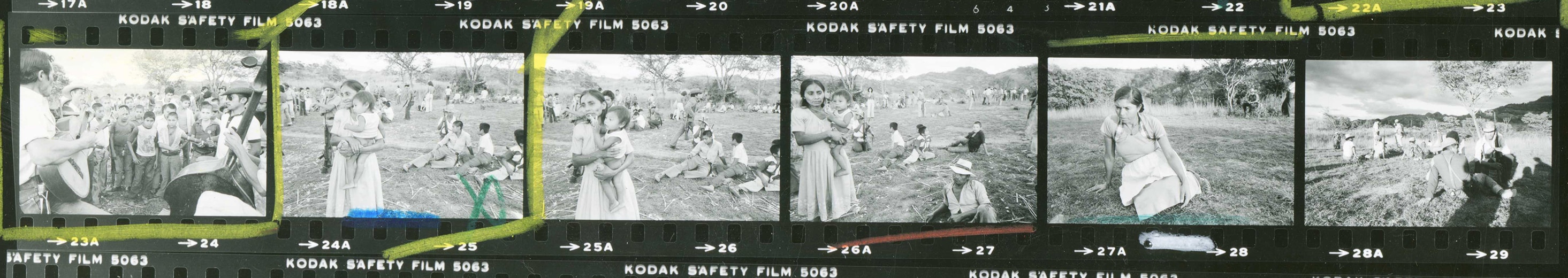

Contact Strip, Rufina Amaya, 1982

What I was able to see when I was standing on the bench looking through the window was that they had everyone blindfolded and handcuffed. They took them out by groups, when they took out the group with the father of my children and brought him to this side, that was when I sat on the bench and cried… I was with my kids, I grabbed them and hugged them crying, but I didn't tell them anything, they stayed inside the house where we were… they took my children from my arms. I had a baby on my chest and 2 soldiers took them all...

I was afraid, and with fear and braveness also told the truth, I pushed myself because of my children. They died and I had to speak or say something, I couldn't do anything when they were dying. So I motivated myself and that is how I told the truth. I denounced and declared for my children and for all those children that cried out for their mothers. They did not deserve to die.

- Rufina Amaya, excerpts published by Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen, El Salvador on Jan 24, 2014, and EMA-RTV Agencia de Noticias Locales Y Ciudadanas de Andalucía on May 3, 2012

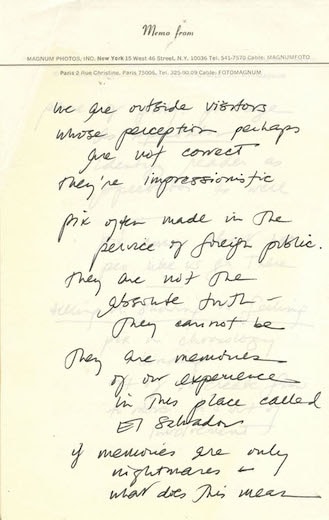

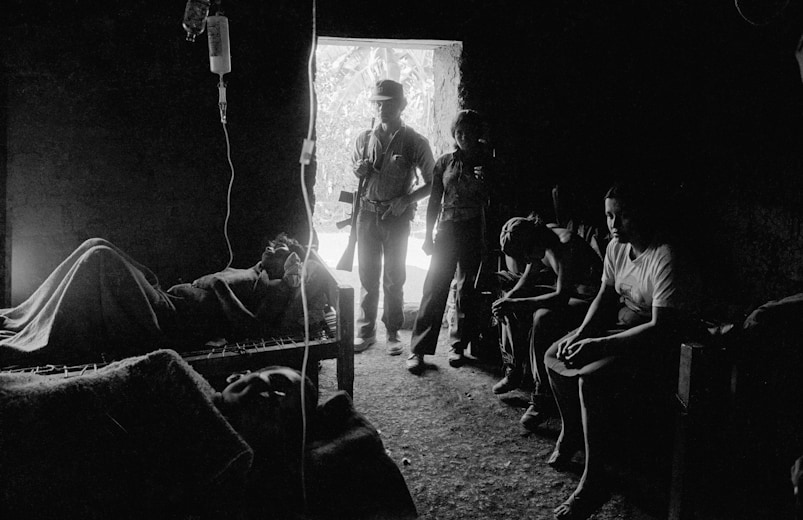

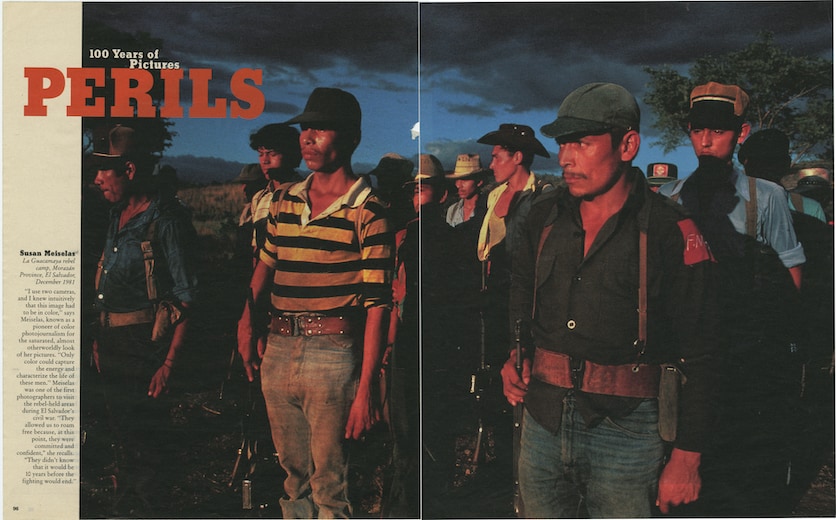

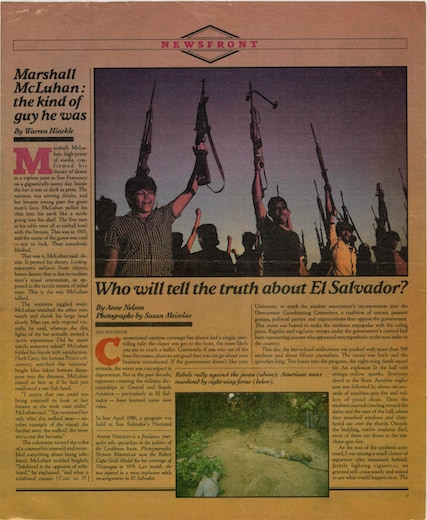

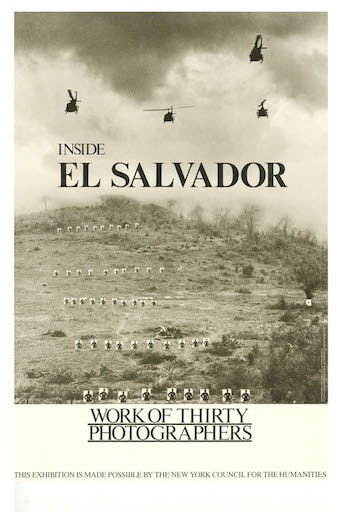

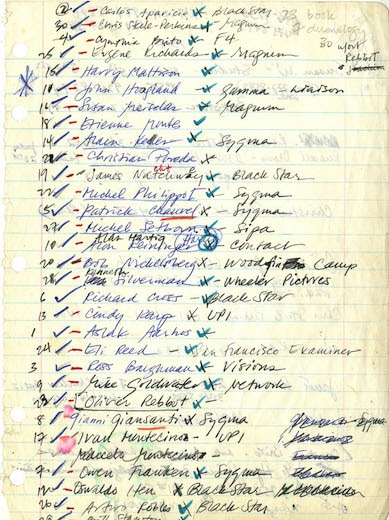

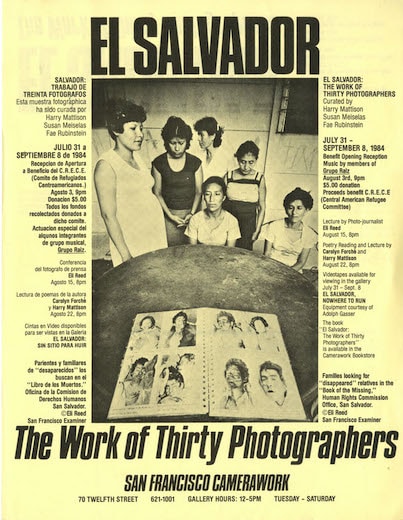

In 1983, at the height of the civil war in El Salvador, thirty international photojournalists covering the conflict contributed to a project to raise awareness about the crisis. They believed that these images, if more widely seen, could facilitate a deeper understanding of the situation in El Salvador and prompt a crucial dialogue about the conflict and America's role in it.

- Kristen Lubben, Editor of In History, 2008

"With the book El Salvador: The Work of Thirty Photographers, the insistence on authorship was a conscious choice; the decision to sign names identified the authors as witnesses. We felt we not only had to take those images but to stand by them. The most brutal images from El Salvador were felt to be the most urgent. To bring those images home to as many Americans as possible meant going beyond the book to create spaces for the images to be seen. So we organized an exhibition to travel to public libraries, secondary schools, storefronts, and places unimagined, as well as museums and galleries. Even though far more people may have seen the images dispersed in the mass media, in the El Salvador exhibition and book, there was greater integrity in the representation of the work.” — words of SM for SPE Exposure, Vol 27.1, 1989.